Summary Note: Connectivity Tax/Fair Share

“Adapt or die!”

- Neelie Kroes, European Commission, 2014 in a speech directed to the EU telecommunications industry

“I think there is an issue that we need to consider with a lot of focus, and that is the issue of fair contribution to telecommunication networks”

- Margarethe Vestager, European Commission vice president, May 2022

“The rules in place for twenty years are running out of steam, and operators no longer have the right return on their investments. It is necessary to reorganise the fair remuneration of the networks”

- Thierry Breton, Internal Market commissioner, May 2022 in an interview with Les Echos

Introduction

The EU Commission considers intervening in the commercial relationship between large Content and Application Providers (CAPs) and Internet Access Providers (ISPs) by introducing a sort of compensation payable by certain content providers whose services are the origin of the major part of data traffic on the telecommunication networks. The proposed compensation is labeled as “connectivity/internet tax,” or “fair share/ contribution,” depending on the positioning in the lobbying battle. The large ISPs have been calling for such initiative for years, claiming that the relationship between global big tech companies and the European infrastructure providers must be brought into balance.[1] The large CAPs strongly oppose the concept, claiming that the traffic is caused by the network’s own customers who pay for the data transport.[2] The EU Commission has previously been opposed to the idea (“adapt or die”)[3] but now seems to be more receptive and is considering ways of how it could be implemented to improve connectivity within the European Union.[4]

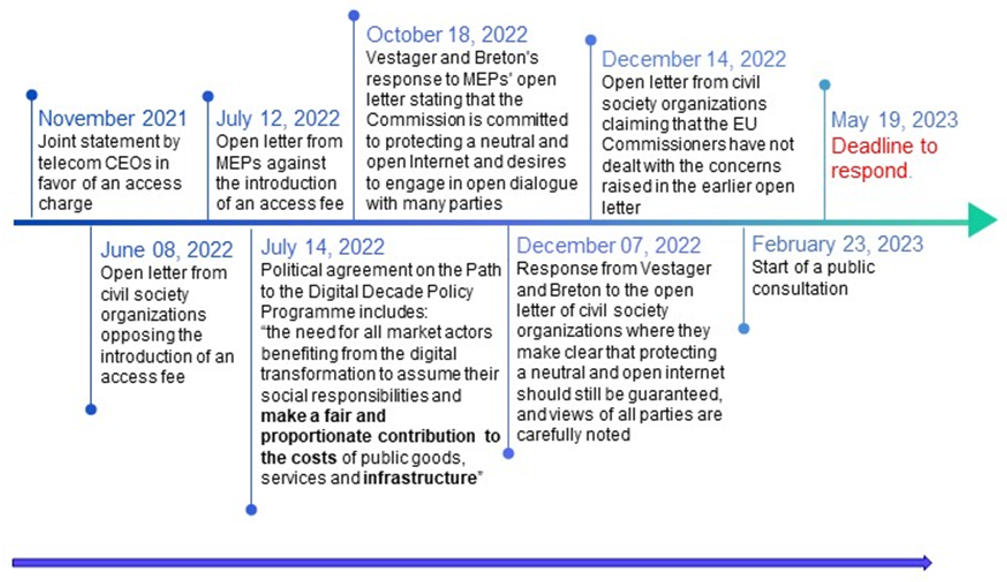

Timeline – What’s Happened So Far?

Background

The volume of data traffic on the networks has undoubtedly grown exponentially over the past decade.[5] To meet the demand, ISPs invest heavily in the roll out of high-speed networks. Those investments reach more than 10 billion EUR a year in Germany and are constantly rising.[6]

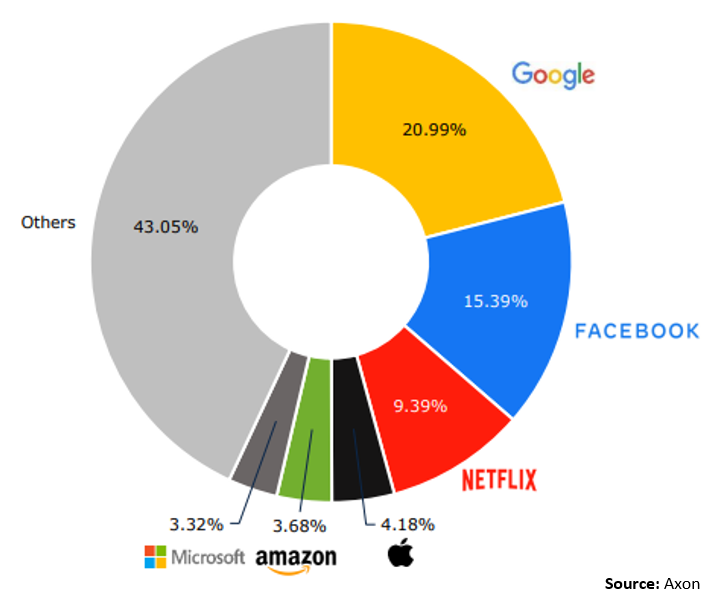

The ISPs see merit in the argument that a large portion of the data traffic growth has been uploaded by a small number of leading CAPs, which, according to ISP research, accounted for more than 50% of all global data traffic in 2021.[7]

Referring to the recently adopted European Declaration on Digital Rights and Principles for the Digital Decade, the ISPs expect the EU to “create appropriate framework conditions so that all market participants . . . make a fair and proportionate contribution to the costs of public . . . infrastructures.[8]”

ISPs suggest that big tech companies are not currently participating in the costly expansion of the networks and believe the profits of big tech companies are generated to a large extent based on the infrastructure they use. Accordingly, they claim access fees as compensation for providing access to the customers of large CAPs and to ensure the expansion of the fiber optic networks and the 5G network.[9]

The CAPs unsurprisingly challenge these arguments and point to the fact that all traffic is ordered by the ISP’s own customers.[10] They believe their content makes the infrastructure more attractive and allows ISPs to charge higher prices for increased/upgraded connectivity. Network customers need flat rates with higher data volumes and pay access fees for such increased connectivity. The key question is whether they pay enough to refinance the network upgrades, and whether it is justified to charge end customers for the increased traffic volume that is driven by their demand—even if the demand is mainly causing traffic uploads by a small number of CAPs. Or would it be “fairer” to also charge the large traffic generating online services? And who would then in the end be paying the bill?

Current Legal Framework and Market Practice

The contractual interconnection relationship between CAPs and ISPs is currently not subject to sector specific telecommunication regulation in Europe or Germany. Since the CAPs do not seek wholesale interconnection to offer broadband access to their customers, no ex-ante or ex-post tariff regime applies to the (potential) interconnection charges. The peering fees charged by any party for the upload of traffic onto another network are therefore subject to commercial negotiations. European and national telecoms regulators have repeatedly analyzed the relevant marketplace and considered the need for regulation. While they identified certain termination bottlenecks and shortcomings with respect to SMP network operators, they so far always concluded that the competition at the retail broadband access level sufficiently remedies the problems on the wholesale interconnection level, noting that no significant complaints have been brought to their attention.[11]

There are two main charging methods available for interconnection-like relationships: the “bill & keep” model and the “Sending Party Network Pays” (SPNP) model.[12] The most common method in use between CAPs and ISPs is “bill & keep”, i.e., the ISPs only charge their end‑customer and not the CAP. But there are exceptions, and the outcome of the commercial bargaining may also depend on the size or dominance of the ISP, in particular the number of customers that can be reached through an ISP. Accordingly, a few market dominant incumbent players have managed to impose the SPNP model on CAPs, where the sending company must pay an access fee to the network infrastructure operator.

Content Delivery Networks (CDN)

Big tech companies normally use Content Delivery Networks (CDNs) in the target area to enhance quality and speed of content delivery to the end user.[13] CDNs serve as aggregators of content and typically use a system of caching servers that enable a more local storage and distribution of content from interconnection points located closer to the end users. Generally, a CDN is a system of servers, deployed at the edge of (or within) the terminating ISPs network, that CAPs can use to distribute their content. To increase efficiency and reduce costs, big tech companies combine CDNs with their own or rented backbone infrastructure that allows routing data locally. As they do not offer or provide connectivity to end-customers and are not resellers of wholesale connectivity products, these networks do not qualify as public telecommunications networks. The traffic coming from these networks is often largely coming from one single CAP. Consequently, the customers receive the content from a server that is either inside of, or directly connected to their ISP’s network within their local region. By reducing the ISP network’s impact on the overall (end-to-end) quality, CDNs increase the end user’s perceived service quality when, for example, they are streaming videos while at the same time reducing transit costs for the ISPs.

Is Net Neutrality at Stake?

One of the key arguments against the proposed connectivity contribution for CAPs is its alleged incompatibility with network neutrality.[14] Yet net neutrality is a complex requirement, and this argument is hardly ever specified or explained in detail. Undoubtedly, the transport of traffic originating from all CAPs is subject to the net neutrality provisions of the open internet regulation (Regulation EU 2015/2120 of November 25, 2015).[15] Article 3(3) of this regulation requires providers of internet access services to “treat all traffic equally, when providing internet access services, without discrimination, restriction or interference, and irrespective of the sender and receiver, the content accessed or distributed, the applications or services used or provided, or the terminal equipment used.”

Network neutrality ensures that every CAP has the same access to infrastructure, that all end users have access to all CAP services, and that all types of traffic are treated equally. That does not permit ISPs to differentiate between data originating from large and small traffic generators. It would likely not even allow the identification of the origin of data, and certainly not a blocking or throttling of data from certain providers who refuse to pay an access fee. The latter is obvious based on the wording of the open internet regulation and BEREC’s guidance,[16] and it was emphasized by the even stricter ECJ Case law on zero rating.[17] Therefore, network neutrality does preclude an access fee for just a few large CAPs, so that data can be transmitted without discrimination and independently of the sender and receiver. An SPNP model for just a few large traffic generators would require determining which provider sends how much data through the networks. This would lead to making data packages identifiable and thus subject to permanent monitoring, clearly in conflict with the net neutrality requirement of networks being sender and receiver agnostic.

On the other hand, network neutrality is not affected by the SPNP model as such, i.e., if a peering charge is applied at an interconnection point between two networks to compensate for an imbalance of data traffic in one and in the other direction. The SPNP concept is common interconnection practice today, and no one would see a violation of net neutrality in such market practice. This is because all traffic at the interconnection point is treated equally, and the charge is applied in relation to the volume of the traffic and not for certain data from certain CAPs. Such interconnection peering charge has no influence on the relationship between individual CAPs and ISPs and no influence on the access of end customers to any content. Thus, network neutrality would not be at stake in this situation.

Now the network provider who is paying the SPNP interconnection charge will ask where the traffic is coming from and will seek to recharge the costs to the network behind the interconnection point that uploads all the heavy traffic. At the end of the network chain, a charge should thus be applied to the large traffic generators if all relevant parties follow this commercial logic. Yet with big tech firms, the situation is not as described. These CAPs do not transmit their data over various networks from interconnection to interconnection to the ultimate ISP who has the end customer. Rather, they use their own CDN, supported by local data centers and back bone infrastructure so that they can upload their data directly to the ultimate ISP, i.e., the ISP who has the direct relationship to the end customer. Such “short cut” to the end customer allows the quality of streaming services we are used to, and the low latency for gaming and other interaction.

Such local access relationship between a CAP and an ISP requires a peering agreement that is subject to commercial negotiations. Depending on the size of the ISP and the overall bargaining power of the parties involved, this may or may not result in a peering charge payable by the CAP. Thanks to the CAP’s own infrastructure, the ISP would normally not carry the CAP data over longer distances, and the data upload per any of the multiple local interconnection points may not be too significant. Further, the CAPs have opened their own infrastructure to ISPs so that they can route their own traffic over the CAP/CDN backbone in times of peak traffic. So, there is some give and take in this CAP/ISP relationship, and the data is not just moving in one direction. This may be one of the reasons why there is no peering charge applied by many ISPs to CAP traffic over local access points.

A negotiated peering charge in such a situation would probably not violate the net neutrality rules if the charge is applied in a nondiscriminatory way equally to all CAP/CDN access seekers. Offering multiple local access points involves infrastructure costs and maintenance efforts and has related costs, so charges may be justifiable and not just a result of the SMP resulting from the termination bottleneck. Moreover, local CAP/CDN access charges are equivalent to SPNP peering charges at the network interconnection level in case of heavy one-directional traffic upload.

A peering agreement that allows CAPs with CDN/backbone infrastructure to connect to the ISP networks on multiple local interconnection points results in faster access to the ISP customers with higher quality compared to CAPs without own infrastructure. In this situation, the superior streaming quality is due to the CAPs own infrastructure and is not the result of a different treatment of the data traffic by the ISP. Only if the multiple local access points would trigger a charge, which is unproportionate to the costs for the local access and data transport to the customer, may the charges be questioned as being an abuse of dominance resulting from the termination bottleneck. But this would not be an issue under the EU net neutrality regulation if the charges are non‑discriminatory, infrastructure/access related, and not sender specific.

But why do ISPs call the EU Commission to intervene at all in this situation if interconnection peering charges as well as local access charges are not per se questionable, and if there is a commercial solution available? Would it be fair to increase the charges for those CAPs that have built their own infrastructure to reduce the long-distance traffic over the ISP networks? Looking at the details of the existing CAP/ISP peering relationship, the charges applied today and the infrastructure costs on both sides, the Commission may realize that the situation is more complex than assumed and that there is no simple solution available without disregarding fundamental market principles of the EU.

What Solutions Are Being Discussed?

Considering the market situation described above, it does not seem unrealistic that ISPs can impose peering charges on other ISPs that upload significantly more traffic than they receive based on commercial negotiations and the SPNP model. And it is also market practice that ISPs receiving peering charges from certain CAPs requesting a direct local access can force the big tech companies to compensate for network access and switch to the SPNP model. Even larger ISPs cannot afford losing any of the big tech services on their networks without losing too many customers. The competition on the retail level is intact as BEREC confirmed, and that prevents the termination bottleneck of even the larger ISPs to translate in enough bargaining power to leverage significant access fees.

Another approach is the introduction of a so-called “digital tax,” where possible levies could be charged based on the revenues generated in a market and not the volume of data traffic (e.g., similar to the film levies charged in several member states).[18] This would not raise concerns related to net neutrality and may allow a more equitable distribution among the ISPs. But a “tax‑like” levy would potentially trigger WTO concerns and certainly a strong reaction by the United States in other transatlantic trade relationships. This has prevented the introduction of a “digital transaction tax” that has been discussed over years.

Another option is hardly considered or even mentioned in this context: to impose additional costs on the end-users requesting the traffic. Flat rates with volume caps, like in the mobile market, have a disciplinary effect. If ISPs would introduce new fixed net tariffs with volume caps, heavy users could lose low flat-rate tariffs and potentially have to adjust their consumption level. That would affect only a very small portion of the customers, and whether it would hurt the CAPs and their data heavy business models is an open question.

EU Consultation

On February 23, 2023, the EU Commission launched an “Exploratory Consultation” on “The future of the electronic communications sector and its infrastructure.”[19] Interested parties can respond and submit views until May 19, 2023. The consultation is supposed to be an open dialogue with all stakeholders about the “potential need for all players benefitting from the digital transformation to fairly contribute to the required investments.” The Commission sees a paradox between exponentially increasing traffic volumes and moderate ISP returns and appetite to invest in network infrastructure. It cites the call by ISPs for a contribution of those digital players who generate enormous volumes of traffic. Such contribution would be “fair” as those CAPs would take advantage of the high-quality networks but would not bear the costs of their roll-out. The Commission also quotes the counter arguments, namely that the traffic is requested by the end‑users and the network costs were not necessarily traffic sensitive, the threat to net neutrality, and the way the internet works.

While the questionnaire does not take a position per se, its design and language clearly reveals sympathy with the idea of a contribution by the so-called “large traffic generators” (LTGs). This terminology implies a role of very few big tech companies generating their profit at the expense of infrastructure builders, and many of the questions are designed to trigger a response that this imbalance should be fixed. A chapter with consumer-focused questions emphasizes the need for universal service and affordability of high-speed connectivity, practically ruling out that the consumer who is requesting the increased traffic should pay for it (through volume caps, etc.).

After the regulatory constrain of very large online platforms through the DMA and DSA it would not come as a surprise if the EU Commission would now lay the groundwork for another big U.S. tech focused regulation; this time with a direct financial impact.

[1] ETNO, “ITRs Proposal to Adress New Internet Ecosystem” (September 2012); Joint CEO Statement of Europe’s leading telecommunication companies from November 29, 2021.

[2] Open letter from 34 civil society organizations opposing the introduction of an access charge (June 08, 2022) p. 1, 2.

[3] Speech “Adapt or die” by Neelie Kroes from October 1, 2014.

[4] Vestager Zitat Press Briefing following publication of ETNO Report on May 2, 2022.

[5] According to a study from ETNO commissioned by ISPs, “state of digital communications 2022,” p. 48.

[6] Federal Network Agency for GER only (10.8 billion EUR in 2020); rollout in Europe by all ISPs amounts to more than EUR 50 billion per year according to industry sources (ETNO state of digital communications report 2022, p. 5, 32).

[7] Sandvine, “Global Internet Phenomena Report 2022,” p. 14.

[8] European Commission, “European Declaration on Digital Rights and Principles for the Digital Decade” (January 26, 2022, COM (2022) 28 final) p. 3.

[9] Axon Partners Group, “Europe's internet ecosystem: socioeconomic benefits of a fairer balance between tech giants and telecom operators” (May 2022).

[10] Open letter from 34 civil society organizations opposing the introduction of an access charge (June 08, 2022) p. 1,2.

[11] BEREC, Comments on the ETNO proposal for ITU/WCIT or similar initiatives along these lines, 2012, p. 3.

[12] BEREC, “Comments on the ETNO proposal for ITU/WCIT or similar initiatives along these lines” (November 2012) p. 3.

[13] BEREC, “Report on IP-Interconnection practices in the Context of Net Neutrality” (October 2017).

[14] Among others: Open letter from 34 civil society organizations opposing the introduction of an access charge (June 08, 2022); Open letter from 54 MEPs who are against the introduction of an access fee (July 12, 2022); Verbraucherzentrale Bundesverband, “Gefährdung des offenen und freien Internets” (August 2022).

[15] Official Journal of the EU of November 26, 2015, L 310/1.

[16] BEREC, “Guidelines on the Implementation of the Open Internet Regulation” (BoR (22) 81, June 09, 2022) p.12, 17, 18.

[17] ECJ cases C-854/19 (ECLI:EU:C:2021:675), C-5/20 (ECLI:EU:C:2021:676), C-34/20 (ECLI:EU:C:2021:677) from September 2, 2021.

[18] Netzpolitik, “EU-Regulierung kommt Anfang 2023 ins Rollen” (December 20, 2022).

[19] European Commission, “The future of the electronic communications sector and its infrastructure” (February 23, 2023).

Christoph WagnerCo-Chair Global Film & Entertainment Practice

Christoph WagnerCo-Chair Global Film & Entertainment Practice