In Revised Corporate Enforcement Policy, DOJ Increases Incentives for Voluntary Self-Disclosure and Cooperation

On January 17, 2023, the Assistant Attorney General (AAG) for the Criminal Division of the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ), Kenneth Polite, Jr., announced that DOJ had made “significant changes” to its Corporate Enforcement Policy (the “Policy” or the “CEP”). Most notably, the revised Policy increases the incentives for companies to voluntarily self-disclose misconduct, cooperate with DOJ investigations, and implement timely and appropriate remediation.

AAG Polite emphasized three major changes to the CEP:

- The potential for a company to receive a declination even when “aggravating circumstances” are present, if the company can demonstrate that it:

“Immediately” made a voluntary self-disclosure upon learning of the misconduct;

Had an effective compliance program and system of internal accounting controls that enabled the identification of the misconduct and led to the self-disclosure; and

- Provided “extraordinary cooperation” and undertook “extraordinary remediation.”

- A 25% percent increase in the potential fine reductions that companies can receive under various circumstances; and

- A framework under which every company “starts at zero cooperation credit” and can earn up to the full amount of cooperation credit based on “parameters and factors outlined in the CEP.”

In general, the revised CEP is a positive development that further illustrates DOJ’s commitment to incentivize companies to detect and prevent corporate misconduct, and to cooperate with DOJ when they identify criminal misconduct.

The History of the CEP

For many years, DOJ’s Criminal Division has attempted to incentivize companies to voluntarily self-disclose violations, cooperate with government investigations, and remediate the root causes that led to the misconduct. Before 2016, DOJ provided these incentives primarily on an ad hoc basis and used press releases that included information from the “relevant considerations” sections of corporate enforcement actions to spread the word publicly. In April 2016, DOJ’s Criminal Division announced a one-year “Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA) Pilot Program” intended to motivate companies to voluntarily self-disclose FCPA-related misconduct by offering more concrete and transparent guidance as to how a company could earn fine reductions and other incentives through self-disclosure, cooperation, and remediation. In November 2017, DOJ announced a new “FCPA Corporate Enforcement Policy,” which superseded the FCPA Pilot Program and has been part of DOJ’s policy manual ever since. The CEP (1) created a “presumption that [a] company will receive a declination” when it voluntarily self-discloses, fully cooperates, and timely and appropriately remediates misconduct, absent aggravating circumstances; (2) provided up to a 50% reduction off of the bottom of the U.S. Sentencing Guidelines (USSG) fine range when the company self-disclosed, fully cooperated, and remediated but when such aggravating circumstances were present; and (3) provided for up to a 25% reduction off of the bottom of the USSG fine range when the company fully cooperated and remediated but did not voluntarily self-disclose the misconduct. Originally applicable only to corporate FCPA cases, in March 2018, the Criminal Division announced that it would apply the CEP as non-binding guidance in criminal cases outside the FCPA context. In March 2019, DOJ revised the CEP, but maintained the same declination presumption and potential fine reductions as in the original version.

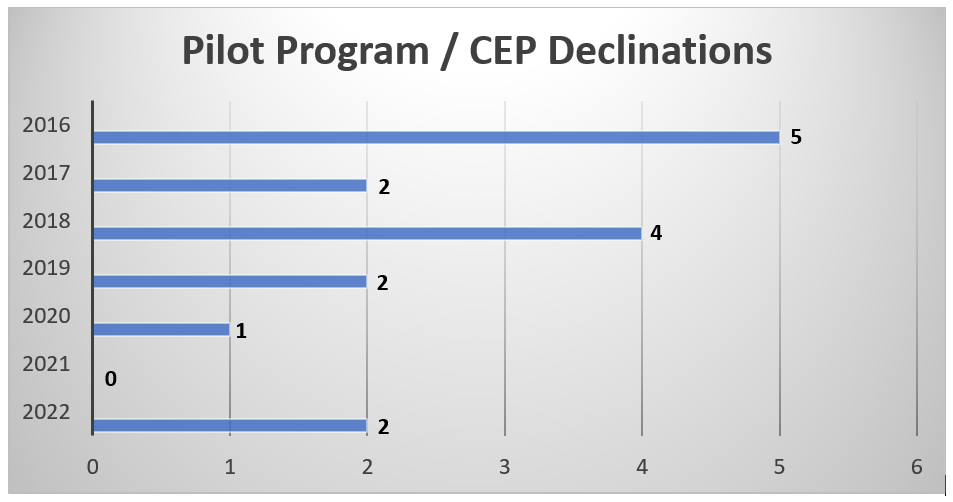

The decision to voluntarily self-disclose a potential criminal violation to DOJ is always among the hardest decisions a company can make. To its credit, DOJ’s Criminal Division has recognized this and, through the CEP, has attempted to offer transparent guidance to incentivize self-disclosures. But many (including us), have questioned whether the CEP finds the right mix of incentives. For example, the Criminal Division’s pre-CEP practices, while less transparent and predictable, arguably offered prosecutors more flexibility in fine reductions and, in the best-case scenario for companies, the ability to provide a full, non-public declination. Companies might have found this potential for a greater reward more enticing than the hard ceilings established in the CEP. Although the available evidence is scant, there is some indication that the CEP might not be having its intended effect, at least to the degree that DOJ might have hoped. For example, between April 2016 and the end of 2022, DOJ issued a total of 16 FCPA-related declinations under the FCPA Pilot Program and CEP, but as illustrated in the chart below, nearly two thirds of those declinations were issued between 2016 and 2018. This naturally raises the question: Why have CEP declinations slowed to a crawl? One potential answer is that companies have not found the CEP’s incentives sufficiently tempting to risk the downsides of self-disclosure (or worse from DOJ’s perspective, that companies have found the CEP to disincentive self-disclosure).

To be fair, this is not an easy task. No one has a crystal ball that will tell them which mix of incentives will optimize corporate behavior. DOJ’s Criminal Division deserves credit for continually working to revisit its policies to try to find the right balance.

2023 Revisions to the CEP

On January 17, 2023, AAG Polite announced that DOJ has made “significant changes” to the CEP. Below we discuss what we believe to be the key revisions, which Polite explained are designed to increase the incentives for companies to voluntarily self-report misconduct to DOJ and to cooperate with DOJ investigations.

Declinations Despite Aggravating Circumstances

As discussed above, under the original CEP, even companies that voluntarily self-disclosed, fully cooperated, and timely and appropriately remediated could not obtain a declination when aggravating circumstances were present. Aggravating circumstances were defined to include, without limitation, involvement by executive management of the company in the misconduct; a significant profit to the company from the misconduct; pervasiveness of the misconduct within the company; and criminal recidivism. AAG Polite recognized that the unavailability of a declination under these circumstances may have led companies and their outside counsel to conclude that “it is more prudent not to disclose this misconduct.”

To reduce this disincentive to self-disclosure, the revised Policy, in AAG Polite’s words, “presents another path for companies facing such a choice.” The revised Policy provides that, although a company will not qualify for a presumption of a declination if aggravating circumstances are present, prosecutors may nonetheless determine that a declination is an appropriate outcome if the company can demonstrate that:

- The voluntary self-disclosure was made immediately upon the company becoming aware of the allegation of misconduct;

- The company had an effective compliance program and system of internal accounting controls at the time of the misconduct and disclosure, which enabled the identification of the misconduct and led to the company’s voluntary self-disclosure; and

- The company provided extraordinary cooperation with DOJ’s investigation and undertook extraordinary remediation that exceeds the respective factors listed herein.

This is an important revision that could indeed induce some companies to come forward and self-report. One potential area for ambiguity is that companies and prosecutors can reasonably disagree over what qualifies as “immediate” disclosure and “extraordinary” cooperation and remediation. For example, a company with a well-functioning compliance system will typically receive many reports of potential misconduct. It would be in neither the company’s nor DOJ’s best interest for the company to self-report every such allegation: not all of them will be actionable or meritorious, and both companies and DOJ should be thoughtful and judicious in how they expend investigative resources. But when a company receives a vague whistleblower report, takes what it believes to be a reasonable amount of time to “kick the tires” on the allegation, and then ultimately decides to self-report shortly after determining that there might be merit to it after all, the question remains whether DOJ will consider this an “immediate” self-report, or whether DOJ will fault the company for not disclosing the initial report the moment it came in? We would like to believe the former, but this type of uncertainty over terms like “immediately” could still cause well-intentioned companies to decide, again in AAG Polite’s words, that it is “prudent not to disclose this misconduct.”

Potentially Higher Fine Reductions

The revised CEP also increases the incentives for companies that might not qualify for a declination, chiefly through offering increased potential fine reductions. As noted above, under the original CEP, the fine reduction for companies that voluntarily self-disclosed, fully cooperated, and timely and appropriately remediated but were not eligible for a declination was capped at 50% off of the low end of the USSG fine range. The CEP now provides that a non-recidivist company that meets such criteria will receive at least 50% and up to a 75% reduction off of the low end of the USSG fine range, while a similarly situated recidivist company will be eligible for the same percentage reductions, but from somewhere above the bottom of the USSG range. In addition, DOJ will generally not require a corporate guilty plea or the appointment of an independent compliance monitor in these circumstances.

The CEP also increases the potential fine reductions for companies that do not self-disclose the misconduct but still fully cooperate and appropriately remediate. As discussed above, the original CEP capped the fine reductions in such circumstances at 25% off of the low end of the USSG fine range. Under the revised CEP, non-recidivist companies that fully cooperate and appropriately remediate will receive up to a 50% reduction off of the low end of the USSG fine range, while similarly situated recidivist companies will be eligible to have that reduction taken off an amount somewhere above the low end.

Baseline: Zero Cooperation Credit

As discussed above, the revised CEP provides for potentially greater credit to companies that cooperate in a Criminal Division investigation. But the CEP also establishes a new framework for evaluating cooperation. As described by AAG Polite, under the revised CEP, “each and every company starts at zero cooperation credit and must earn credit based on the parameters and factors outlined in the [Policy].” In other words, as explained in the revised CEP, companies do not “start[] with the maximum available credit and receiv[e] reduced credit for deficiencies in cooperation.”

Emphasizing that “[a] reduction of 50% will not be the new norm,” AAG Polite stated that the new incentives “will be reserved for companies that truly distinguish themselves and demonstrate extraordinary cooperation and remediation.” As discussed above, reasonable minds can differ as to what counts as “extraordinary,” and the CEP simply states that extraordinary cooperation “exceeds the factors” listed in the CEP, such as timely disclosure of all non-privileged facts relevant to the wrongdoing at issue, proactive cooperation, and timely and voluntary preservation, collection, and disclosure of relevant documents. In his announcement, the AAG offered some additional guidance on how federal prosecutors should distinguish between “extraordinary” and “full” cooperation under the revised Policy. The AAG “note[d] some concepts—immediacy, consistency, degree, and impact—that apply to cooperation by both individuals and corporations, which will help to inform our approach to assessing what is ‘extraordinary.’” The AAG further explained that “extraordinary” cooperation could include cooperation that is immediate and consistently truthful, leads to evidence that prosecutors otherwise could not get, or “produces results, like testifying at trial or providing information that leads to additional convictions.” But the AAG also allowed that “[i]n many ways, we know ‘extraordinary cooperation’ when we see it, and the differences between ‘full’ and ‘extraordinary’ cooperation are perhaps more in degree than kind.” The AAG concluded that “to receive credit for extraordinary cooperation, companies must go above and beyond the criteria for full cooperation set in our policies—not just run of the mill, or even gold-standard cooperation, but truly extraordinary.”

Key Takeaways

- The revisions to the CEP reflect DOJ’s recognition that a company’s decision to self-report misconduct can be difficult and exhibit DOJ’s willingness to refine its policies to try to make the decision to self-report easier.

- On balance, the revised CEP increases the incentives for companies to voluntarily self-report misconduct to DOJ’s Criminal Division, fully cooperate in its investigations, and timely and appropriately remediate in two ways: by increasing the population of companies that are eligible for declinations with disgorgement and by increasing the potential fine reductions for companies that are not.

- As with previous versions of the CEP, there can still be good-faith disagreements between prosecutors and companies as to whether the company is eligible for certain benefits. For example, disputes over whether a company “immediately” reported the misconduct to the Criminal Division or whether the company provided “extraordinary” cooperation are likely in at least some cases. While it is difficult to eliminate the potential for disagreements so as long as the CEP tries to provide prosecutors with flexibility to shape a resolution that best reflects the individual circumstances of each case, this same potential for disagreement will continue to cause some companies to have second thoughts about whether to voluntarily self-disclose misconduct or to undertake certain types of cooperation.

- We encourage more communication and engagement between DOJ and the business community on these types of issues to maintain an open dialogue on how DOJ’s policies are affecting companies. This latest round of revisions has demonstrated DOJ’s willingness to react to feedback from the business community. To that end, we expect continued discussions on these issues to identify additional areas that may call for further refinement.

Charles Tso, a law clerk in Morrison & Foerster LLP’s New York office, contributed to this alert.