The Lifecycle of a Voluntary Carbon Credit

Introduction

The burgeoning voluntary carbon credit (“VCC”) market presents a clear opportunity for tackling carbon emissions by allowing individuals, countries, and corporates to purchase credits to offset their own emissions and thus support projects that are reducing the overall carbon footprint on our planet. Growing volumes of VCCs are being purchased by the private sector, where the spotlight on corporate social responsibility and industry leadership has increased the commitment to environmental issues. It has been reported that the VCC market will need to increase up to 15 times by 2030 to support the goal of limiting the average rise in temperature this century to 1.5 degrees Celsius[1].

The Taskforce on Scaling Voluntary Carbon Markets (“TSVCM”), initiated by Mark Carney, UN Special Envoy for Climate Action and Finance, has been leading attempts to grow the VCC market to help achieve the goals of the Paris Agreement of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (the “Paris Agreement”).

This article focuses on the lifecycle of a VCC[2] and legal issues relevant to developing this market.

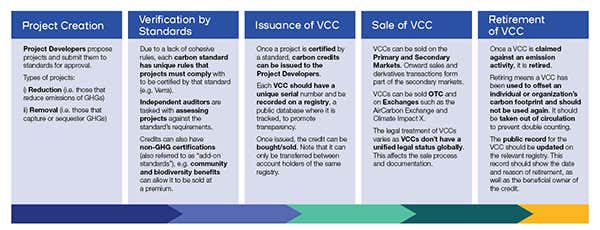

Relevant Stages in the Lifecycle of a VCC

1. Project Creation

VCCs allow carbon dioxide (“CO2”) producers to offset their emissions by purchasing credits associated with projects targeting (i) the reduction of CO2 or other greenhouse gases (“GHGs”) or (ii) the removal of CO2 or GHGs from the atmosphere.

Examples of such projects include:

- Renewable energy projects;

- Energy efficiency schemes;

- Tree-planting schemes; or

- Forestry protection.

In order to account for a valid calculation to offset emissions, there must be an underlying methodology for measuring and verifying the emission reductions associated with the project. For example, a project concerning energy efficient cooking stoves will follow specific rules when calculating the level of CO2 saved and therefore the number of VCCs produced.

2. Assessment and Certification

Carbon standards (each, a “Standard”) are organisations that establish that a project meets its stated reduction and removal objectives and can therefore have VCCs issued. Although the VCC market is fragmented, a number of Standards have emerged as prominent players in the market, including Verified Carbon Standard, managed by Verra, and Gold Standard.

Each Standard has unique rules that projects must comply with to be certified by that Standard. However, generally, Standards require that the emissions reduction/removal is:

- Additional – i.e. would not have occurred in the absence of the market for the project;

- Permanent;

- Not overestimated;

- Not claimed by another entity; and

- Not associated with significant social or environmental harms.

Generally, to generate VCCs:

1. A project developer must compile a project description to demonstrate how the project meets the Standard’s requirements; and

2. A Standard-accredited third-party validation and verification body (a “Verifier”) must then ensure relevant requirements have been met by the project, typically including on-site evaluations.

An ambition of the TSVCM is to remedy “difficulties (both real and perceived) in quality and integrity of the credits”, through developing “Core Carbon Principles” and a governance body to evaluate which Standards may issue VCCs labelled with these Core Carbon Principles[3].

3. Creation and Issuance of VCCs

Once the assessment process is complete, the Standard’s registry can issue VCCs to the project developer’s account. The VCCs are subject to ongoing monitoring and reporting requirements and can continue to be generated and issued for the duration of a crediting period. A crediting period is the time in which GHG emissions reductions or removals are eligible for the issuing of corresponding credits.

Each VCC generally corresponds to one metric ton of reduced or removed CO2 or equivalent GHG. Each VCC should be given a unique identifying serial number that enables clear traceability and auditing, and should be tracked in a public database by the registry to ensure transparency.

4. Sale/Purchase of a VCC

Once the VCC is issued, it can be bought and sold directly to end buyers or through a broker or exchange. It is also possible to trade VCC derivatives. There is currently no widely recognized standard form of template documentation, but industry bodies are currently consulting on possible templates and this is another ambition of the TSVCM[4].

Whether VCCs are characterized as property or contractual rights in the relevant jurisdiction(s) impacts the following key legal considerations for trading VCCs:

a) Documentation required for effective transfer (e.g. a sale of property or a novation/assignment of rights);

b) Documentation required for effective security (e.g. an assignment over rights); and

c) Remedies that might be available if a VCC is misappropriated (e.g. equitable remedies after tracing of property).

A recent ISDA paper[5] states that “an authoritative legal statement, targeted legislative amendments and/or regulatory guidance” would contribute to greater legal certainty and market confidence.

5. Retirement

VCCs can change hands multiple times before they are permanently retired. Buyers that retire a VCC can claim the emissions reductions towards an emissions commitment or target. Once retired, the legal interest that it in effect represented has been used, has been exhausted, or ceased to exist. In any case, records should reflect that the VCC has been retired or cancelled and this usually occurs when a serial number of the VCC is stored in an independent database and taken out of circulation, never to be transferred or used again.

The unregulated nature of the retirement of a VCC poses fundamental questions to potential investors over the issue of greenwashing. A particular issue is “double counting”. Double counting is a situation in which the same emissions reduction or removal is claimed twice. This is a potential issue for investors who are concerned about the validity of VCCs in achieving net zero goals. There has been much discussion on this topic and the TSVCM Phase II Report states, “The Taskforce recommends that potential technology solutions be explored and considered which can help avoid double counting / claiming / use (e.g. blockchain-based logs; reference number systems)”.

6. Interaction with Paris Agreement

Article 6 of the Paris Agreement envisions a global carbon market to help implement states’ nationally determined contributions, and following the 2021 UN Climate Change Conference (“COP 26”), various advance unedited versions of decisions have been published describing the mechanics[6] of a market.

Article 6 of the Paris Agreement attempted to tackle the double counting issue for particular credits issued under its provisions. In the context of each state party to the Paris Agreement achieving its nationally determined contributions, Article 6 clarifies that any time an emissions reduction is issued under Article 6 and transferred abroad, a corresponding adjustment needs to be made to the host country’s emissions tally to account for the transfer of savings to be used by another state.

While the negotiated mechanics of Article 6 of the Paris Agreement are still new and require action from each state party, key VCC market participants such as Verra and Gold Standard are looking toward potential integration with the existing VCC market:

1. Verra states on its website that it “plans to make an Article 6 label and associated guidance available now that Article 6 of the Paris Agreement has been finalized at COP26 in November 2021”[7].

2. Gold Standard states on its website that “In October 2021, we opened a further consultation on the process we will introduce to enable project developers to attach host country authorisations under Article 6 to their credits, opening up new opportunities for the use of these credits in the voluntary market, CORSIA and towards national targets”[8].

This aligns with the TSVCM objective that “Once rules are negotiated, the voluntary market should comply with the rules of the Paris Agreement and Article 6”[9].

Haania Amir, London Trainee Solicitor, contributed to the drafting of this alert.

[1] Taskforce on Scaling Voluntary Carbon Markets Phase II Report, 8 July 2021 (the “TSVCM Phase II Report”).

[2] The descriptions herein are generalized and may not reflect every VCC in the market.

[4] The TSVCM Phase II Report states “For the voluntary carbon market to scale & operate effectively, there will need to be a core reference contract”.

[5] International Swaps and Derivatives Association: Legal Implications of Voluntary Carbon Credits, December 2021.

[6] Decision -/CMA.3 Guidance on cooperative approaches referred to in Article 6, paragraph 2, of the Paris Agreement; Decision -/CMA.3 Rules, modalities and procedures for the mechanism established by Article 6, paragraph 4, of the Paris Agreement; Decision -/CMA.3 Work programme under the framework for non-market. approaches referred to in Article 6, paragraph 8, of the Paris Agreement.

[7] Verra’s Verified Carbon Standard - VCU Labels.

Practices

Industries + Issues