OFAC Year in Review 2021 – Part 1

2021 was a year of transition in the United States and for the U.S. Department of the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC). OFAC’s year, while busy, was far different from 2020, as the Biden Administration’s political team at the Treasury took office, conducted a sweeping sanctions review, and began implementing the Administration’s sanctions policy priorities. Although the Biden Administration demonstrated its intent to remain tough on China and Russia, it slowed the expansion of sanctions on Iran and Venezuela, emphasized multilateral efforts to reengage Iran and work with allies on human rights and other sanctions program priorities, and spotlighted ransomware and virtual currency sanctions compliance issues and best practices.

Each year we reflect on the most significant U.S. sanctions developments of the past year in a multi-part series. This Part One summarizes OFAC’s activities and provides programmatic updates from 2021. Part Two will summarize OFAC’s enforcement actions last year and their key lessons.

I. 2021 Summary Numbers

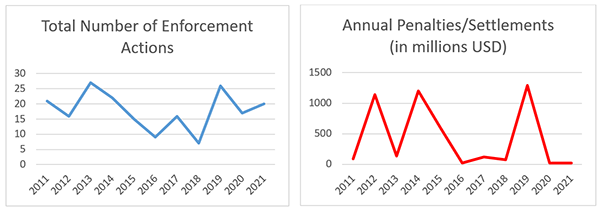

OFAC energetically pursued sanctions enforcement and targeting in 2021. It imposed over $20.8 million in total monetary penalties/settlements across 20 enforcement actions announced in 2021, showing greater activity than 2020’s 17 public actions but for a lower total penalty amount than the $23.6 million in fines imposed in 2020. The graphs below show OFAC’s 2021 enforcement activity and how it compares to the annual totals from the past decade.

OFAC also issued 765 new designations (i.e., imposition of full blocking sanctions on individuals or entities) in 2021, as reported by the Center for New American Security (CNAS). OFAC issued these designations across its sanctions programs, with the highest concentration in the Global Magnitsky program (over 170), the Belarus program (around 100), and the Burma program (76). At the same time, OFAC was active in removing designations – with over 700 delistings in 2021 as compared to around 200 in 2020 – likely as part of OFAC’s continuing sanctions program maintenance and as a result of the Biden Administration’s comprehensive review of sanctions programs in the first half of the year. For more information on these statistics, we recommend that you visit CNAS’ Sanctions by the Numbers.

The Treasury Department released statistics quantifying the growth of U.S. sanctions in its 2021 Sanctions Review (the Review). As noted in our previous client alert, net sanctions designations increased 933% over the last 20 years to expand OFAC’s sanctions lists from 912 sanctioned parties in 2000 to 9,421 in October 2021. The last two decades also saw an explosion of OFAC sanctions authorities, which grew from 69 (2000) to 176 (2021). Aside from the numbers, the Review also highlighted that OFAC continues to pursue multilateral designations in coordination with U.S. allies and partners when possible. This multilateral approach is bearing fruit. As noted by Castellum.AI in its review of 2021 sanctions designations targeting global human rights abusers by Western U.S. allies, the United Kingdom issued 35 designations and the European Union issued 22 under their more recent human rights sanctions programs.

II. Significant OFAC Developments in 2021

A. China

1. Chinese Military Companies

In his final week in office in January 2021, President Trump issued Executive Order (E.O.) 13974, which amended E.O. 13959, the original E.O. issued in November 2020 that prohibited U.S. persons from investing in securities of any identified “Communist Chinese military company” (CCMC). The amended E.O. further prohibited transactions involving U.S. persons in CCMC securities and required divestment of all such securities within a year of an entity being listed as a CCMC. However, it clarified only some of the questions arising from the vague and somewhat confusing original E.O. 13959.

In June 2021, as detailed in our alert, President Biden further amended E.O. 13959 in E.O. 14032. This new E.O. and related OFAC guidance provided welcomed clarity on OFAC’s CCMC sanctions (renamed CMIC for “Chinese Military-Industrial Complex”). The new E.O. both expanded and limited these sanctions by: (1) broadening the categories of companies and their subsidiaries that could be targeted to include those linked to the “military-industrial complex” and “surveillance technology sector” of China; (2) extending the divestment period for investments in companies deemed to operate in China’s defense and surveillance technology sectors, as identified on OFAC’s (renamed) Non-SDN Chinese Military-Industrial Complex Companies List (the NS-CMIC List), to June 2, 2022; (3) revoking amendments to E.O. 13959 previously implemented in E.O. 13974; and (4) clarifying that U.S. persons are not prohibited from facilitating investments in securities of companies on the NS-CMIC List by non-U.S. investors. There are currently 68 Chinese companies listed on the NS-CMIC List (which contains name variants for a total of 205 entries), concentrated in high-tech sectors including such as aerospace, artificial intelligence, electronics, defense technology, and telecommunications.

2. Xinjiang

In 2021, the U.S. government continued its efforts to address perceived human rights abuses in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (Xinjiang) and elsewhere in China through a whole-of-government approach. OFAC added four current and former Chinese government officials connected to Xinjiang to its List of Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons (SDN List) and a related surveillance entity to the NS-CMIC List. Separately, the U.S. Department of Commerce’s Bureau of Industry and Security added 19 companies connected to Xinjiang to its Entity List in 2021, barring provision of any items subject to the Export Administration Regulations to those entities.

In July 2021, the Departments of Commerce, Homeland Security, State, and Treasury issued an updated Xinjiang Supply Chain Business Advisory highlighting compliance risks for continued dealings involving Xinjiang, given the Secretary of State’s determinations of widespread forced labor and other egregious human rights abuses. This advisory warns that “businesses and individuals that do not exit supply chains, ventures, and/or investments connected to Xinjiang could run a high risk of violating U.S. law.”

Congress also passed related legislation, with both houses passing different versions of a “Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act.” President Biden signed a compromise bill in December 2021 (Pub. L. 117–78). This law prohibits the import of “goods produced in whole or in part by forced or compulsory labor,” and establishes a rebuttable presumption that all “goods mined, produced, or manufactured wholly or in part in [Xinjiang]” are prohibited imports. This law also amends the Uyghur Human Rights Policy Act of 2020 by expanding those foreign persons the President may target with asset blocking sanctions and visa restrictions to include those the U.S. Government deems responsible for “[s]erious human rights abuses in connection with forced labor.”

3. Hong Kong

In 2021, OFAC – together with the Department of State – further implemented sanctions against Chinese and Hong Kong officials for activities the United States deemed as eroding China’s obligations to Hong Kong under the Sino-British Joint Declaration of 1984 establishing Hong Kong’s relative independence. In January 2021, OFAC published the Hong Kong-Related Sanctions Regulations, implementing sanctions authorized by E.O. 13936. In January and July 2021, OFAC designated six and seven Chinese and Hong Kong officials, respectively, pursuant to E.O. 13936. Following each of those rounds of designations, the Department of State updated its report under Section 5(a) of the Hong Kong Autonomy Act (HKAA) (described in detail in our alert). Further, in March 2021, the Department of State added 24 SDNs to its report, with another five following in December 2021, causing OFAC to implement secondary sanctions on those SDNs pursuant to the HKAA. As of the end of 2021, there were 42 SDNs designated by OFAC pursuant to E.O. 13936, and of those, 39 are also subject to secondary sanctions. The SDNs not subject to secondary sanctions are no longer actively serving officials.

In July 2021, the Departments of Commerce, Homeland Security, State, and Treasury published a business advisory warning companies and individuals operating in Hong Kong of heightened risks related to doing business there, including threats to personal freedoms, data privacy and security, and press freedoms. The advisory warns of increased sanctions exposure related to heightened risks of (1) additional U.S. sanctions being imposed against China for violating Hong Kong’s autonomy and (2) potential retaliation from the Chinese government against companies that comply with sanctions imposed by the United States and other countries.

B. Russia

1. Nord Stream 2

In 2021, OFAC designated more than 30 individuals and entities and identified blocked vessels related to Nord Stream 2 – an undersea pipeline bypassing Ukraine that is intended to bring natural gas from Russia to Germany – pursuant to the Protecting Europe’s Energy Security Act (PEESA). Despite these actions, the Biden Administration was widely criticized in Congress (but praised in German political circles) for its failure to take more decisive action to prevent the completion of Nord Stream 2. As we previously discussed, U.S. Secretary of State Blinken announced in May 2021 a waiver of sanctions on the most significant entities and individuals named in a report to Congress required under PEESA identifying involved vessels, entities, and individuals for menu-based sanctions, including the company overseeing the project and its CEO. Secretary Blinken stated that “[U.S.] opposition to the Nord Stream 2 pipeline is unwavering,” but defended the waiver as “consistent with the President’s pledge to rebuild relationships with our allies and partners in Europe.”

Although the Biden Administration apparently waived these sanctions to repair relations with Germany, Senate Republicans introduced legislation to require President Biden to impose sanctions on Nord Stream 2, and the House passed an amendment to the 2022 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) with the same effect, as we discussed here. However, there was no vote on the Senate bill, and the Nord Stream 2 sanctions were dropped from the final 2022 NDAA.

Future legislation may create new or modify existing U.S. sanctions related to the pipeline’s development and operation. For example, the “The Defending Ukraine Sovereignty Act of 2022,” introduced by Sen. Bob Menendez (D-NJ) in early January 2022 in response to Russia’s buildup of troops on the Ukrainian border, would require designation of entities and corporate officers involved in completing Nord Stream 2. We summarize this bill and the companion legislation in the House in our alert.

2. New Sanctions for Specified Harmful Activities

On April 15, 2021, the Biden Administration authorized new sanctions on Russia through E.O. 14024, “Blocking Property With Respect To Specified Harmful Foreign Activities Of The Government Of The Russian Federation.” Unlike previous Russia-related sanctions targeting discrete issues, E.O. 14024 authorizes imposing sanctions on individuals and entities related to a broad swath of malign conduct, including Russian efforts to undermine democratic elections and institutions, facilitate malicious cyber-enabled activities, foster transnational corruption to influence foreign governments, pursue extraterritorial activities targeting dissidents and journalists, and undermine security in countries and regions important to U.S. national security. Our previous alert details these April 2021 sanctions.

OFAC subsequently used E.O. 14024 to designate nine entities and two individuals and to impose additional restrictions on Russian sovereign financing. OFAC’s new Directive 1 for this E.O. – not to be confused with its other Directive 1 related to sectoral sanctions under E.O. 13662 – prohibits (1) participation by U.S. financial institutions in the primary market for ruble- and non-ruble-denominated bonds issued after June 14, 2021 by Russia’s Central Bank, National Wealth Fund, or Ministry of Finance, and (2) any lending by U.S. financial institutions to Russia’s Central Bank, National Wealth Fund, or Ministry of Finance.

OFAC separately designated 32 Russian entities and individuals under other authorities for their roles in attempting to influence U.S. elections; five individuals and three entities for activities related to the ongoing crisis in Crimea; and six technology companies for their roles in supporting Russian espionage campaigns (such as the SolarWinds cyberattack). President Biden also announced the expulsion of ten Russian diplomats from the United States. These actions represented a significant toughening of sanctions against Russia and signal more to come, particularly as Russia continues to amass its troops on Ukraine’s borders.

C. Iran

The Biden Administration has attempted to renew the “nuclear deal” with Iran, but the situation remains complicated and any resolution remains unclear. Although the new, deeply conservative Iranian government was willing to negotiate in 2021, Iran continues to point to U.S. sanctions – which significantly disrupted the Iranian economy under the Trump Administration – as a major obstacle for its willingness to negotiate and reach a new agreement.

While there were no major programmatic shifts related to Iran last year, the Biden Administration’s use of the Iran sanctions program has been markedly different than its predecessor. In 2020, OFAC made nearly 300 Iran-related designations. In 2021, OFAC made fewer than 60 Iran-related designations, with most occurring during President Trump’s final weeks in office. Separately, the Department of State designated Ansarallah (a.k.a. the “Houthis”), a Yemeni rebel group backed by Iran, as a Foreign Terrorist Organization in January 2021. Although OFAC concurrently authorized limited humanitarian activities involving Ansarallah, Secretary of State Blinken revoked the terrorist designation of Ansarallah in February 2021 after calls to do so from aid groups. OFAC also issued general licenses in 2021 authorizing exports and related dealings involving (i) COVID-19-related goods, technology, and services, and (ii) virtual education services and software in response to the ongoing pandemic.

D. Belarus

As noted above, OFAC spent significant energy on the Belarus program in 2021 and designated around 100 targets (accounting for more than 10 percent of all OFAC designations last year). Responding to the continuing devolution of the political situation in Belarus following the fraudulent August 2020 election of Belarusian President Lukashenka and the forced landing of a commercial aircraft flying over Belarus to arrest an opposition leader, President Biden expanded the scope of Belarus sanctions in August 2021 with E.O. 14038, “Blocking Property of Additional Persons Contributing to the Situation in Belarus.” This E.O. refers to “long-standing abuses aimed at suppressing democracy and the exercise of human rights and fundamental freedoms in Belarus” as well as “the disruption and endangering of international civil air travel” and authorizes sanctions on officials of the Government of Belarus and individuals and entities engaged in proscribed activities (e.g., destabilizing activity, electoral fraud, and actions limiting access to the internet or media in Belarus) or operating in a wide range of sectors of the Belarusian economy, including the defense, energy, construction, security, and transportation sectors. OFAC designated 66 individuals and entities under the new E.O. authorities in 2021.

The Biden Administration also imposed prohibitions on dealings in Belarusian sovereign debt. In December 2021, OFAC issued Directive 1 under E.O. 14038, prohibiting transactions in, provision of financing for, and other dealings within U.S. jurisdiction in new debt with a maturity of greater than 90 days, issued on or after December 2, 2021, by the Belarusian Ministry of Finance or Development Bank of the Republic of Belarus.

E. Re-Imposition of Sanctions on Burma

In February 2021, President Biden issued E.O. 14014 to address the crisis in Burma following the military coup. (The United States previously maintained significant sanctions on Burma for decades prior to President Obama’s termination of the program in 2016, as detailed in our alert.) E.O. 14014 authorizes blocking sanctions on parties operating in the defense sector of Burma or involved in, among other things, undermining democracy, threatening peace, security, or stability, limiting free speech, or serious human rights abuses. E.O. 14014 also authorizes designating officials of the military, security forces, or the government of Burma.

OFAC designated 76 individuals and entities in Burma throughout 2021, including both the military government in Burma (the State Administrative Council) and two major Burmese military holding companies (Myanma Economic Holdings Public Company Limited (MEHL) and Myanmar Economic Corporation Limited (MEC) that control significant segments of the Burmese economy. As a result of the major impact of these designations, OFAC also issued five broad general licenses authorizing wind-down activities and activities of international entities and non-governmental organizations (NGOs), among other things.

Secretary Blinken noted that the U.S. government calibrated the new Burmese sanctions to target coup participants without worsening the humanitarian plight of the Burmese people. Burma General License 3, issued in March 2021, authorized transactions in support of NGOs’ humanitarian projects to support basic human needs, democracy building, education, noncommercial development, and environmental and natural resource protection in Burma. This license, along with the many COVID-19-related licenses OFAC issued in 2021, exemplifies the Biden Administration’s efforts to mitigate the humanitarian impact of sanctions.

F. Afghanistan

In August 2021, the Taliban advanced throughout Afghanistan, moved into Kabul, the capital, and effectively took over the country with a de facto government. Both the Taliban and the Haqqani Network, a group affiliated with the Taliban and involved in the new government, are individually designated as Specially Designated Global Terrorists (SDGTs) under E.O. 13224, along with senior members of both groups, although the Government of Afghanistan has not been identified publicly as a sanctioned entity by the United States. While dealings between U.S. persons and the Government of Afghanistan remain in somewhat of a legal limbo, given the Taliban control, OFAC has stressed that there are no OFAC-administered sanctions prohibiting activities in Afghanistan, the export or reexport of goods or services to Afghanistan, or moving money into and out of Afghanistan, so long as those activities or transactions do not involve sanctioned individuals or entities. To facilitate the flow of humanitarian support into Afghanistan, OFAC has issued General Licenses 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, and 19, authorizing otherwise prohibited activities involving the Taliban or Haqqani Network related to humanitarian assistance, including the activities of international and non-governmental organizations as well as the provision of agricultural commodities, medicine, and medical devices. OFAC has provided clarifying public guidance through its answers to frequently asked questions and a Fact Sheet.

G. Ethiopia

In September 2021, President Biden issued E.O. 14046, “Imposing Sanctions on Certain Persons With Respect to the Humanitarian and Human Rights Crisis in Ethiopia,” declaring a national emergency to deal with the widespread humanitarian crisis resulting from the ongoing violent conflict in northern Ethiopia. E.O. 14046 authorizes the imposition of sanctions on any foreign individual or entity (including government entities and leaders) determined to have engaged in actions or policies that threaten the peace, security, or stability of Ethiopia. OFAC designated the Eritrean Defense Forces as well as two individuals and three entities under this authority, but it also clarified that its “50 Percent Rule” does not apply to entities blocked pursuant to E.O. 14046. To avoid potential humanitarian-related impacts, OFAC issued General Licenses 1, 2, and 3 for certain activities of international and non-governmental organizations and transactions related to agricultural commodities, medicine, and medical devices.

H. Nicaragua

In November 2021, President Biden signed into law the Reinforcing Nicaragua’s Adherence to Conditions for Electoral Reform Act of 2021 (Pub. L. 117-54) after the government of President Ortega imprisoned dozens of opposition members – including seven presidential candidates – ahead of national elections. This law requires the U.S. Departments of State and the Treasury to develop a coordinated strategy to align diplomatic efforts and new targeted sanctions to support free and fair elections. In particular, it directs consideration of whether nine categories of individuals, including officials in the Ortega administration, family members of President Ortega, related party members, and other senior government officials warrant designation. Days after passage, OFAC designated the Public Ministry of Nicaragua and nine government officials pursuant to E.O. 13851, “Blocking Property of Certain Persons Contributing to the Situation in Nicaragua,” and the Nicaragua Investment Conditionality Act of 2018. Another six designations of government officials followed in early January 2022, timed to coincide with President Ortega’s inauguration.

I. Technology Sector

1. Ransomware

In 2021, the Biden Administration used sanctions as part of its approach to curb increasing ransomware attacks. In one example, as part of a coordinated response to the REvil ransomware group (also known as Sodinokibi), OFAC designated two REvil actors for their roles in perpetuating ransomware incidents against U.S. government entities and private sector companies in November 2021. Our previous client alerts (here and here) outline related guidance and discuss the designations and programmatic updates by the U.S. government.

In September 2021, OFAC released an Updated Advisory on Potential Sanctions Risks for Facilitating Ransomware Payments, highlighting that numerous ransomware groups and other malicious cyber actors are sanctioned and that companies making or facilitating ransom payments risk violating U.S. sanctions. OFAC also stated in this advisory that any actions to improve cybersecurity practices, such as those highlighted in the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) September 2020 Ransomware Guide, would be viewed as a mitigating factor in determining the appropriate enforcement response to any apparent sanctions violations (and that OFAC would be more likely to respond with a non-public response such as a no action or cautionary letter).

2. Virtual Currency

In 2021, OFAC focused on sanctions compliance for virtual currency and on virtual currency’s relationship to illicit actors, particularly its use by ransomware actors. As we discussed, OFAC designated virtual currency exchange SUEX in September 2021 under E.O. 13694, “Blocking the Property of Certain Persons Engaging in Significant Malicious Cyber-Enabled Activities,” for materially supporting criminal ransomware actors. In November 2021, OFAC also designated virtual currency exchange Chatex for facilitating financial transactions for ransomware actors and three related companies for providing infrastructure.

OFAC also published Sanctions Compliance Guidance for the Virtual Currency Industry to help the virtual currency industry navigate and comply with OFAC sanctions. In it, OFAC offers both practical guidance (e.g., how to “block” virtual currency) as well as a reminder that U.S. sanctions apply to virtual currency in the same way as fiat currency. OFAC notes that companies in the virtual currency industry are encouraged to develop and implement risk-based sanctions compliance programs that include list-based and geographic screening.

2021 was an extraordinary and transitional year in many respects, including in the world of sanctions. MoFo’s National Security Practice would be happy to discuss any of the issues raised in this alert in more detail and looks forward to keeping our readers current on key OFAC developments in 2022.

John E. SmithPartner

John E. SmithPartner Brandon L. Van GrackPartner

Brandon L. Van GrackPartner B. Chen ZhuPartner

B. Chen ZhuPartner Felix HelmstädterPartner

Felix HelmstädterPartner Nathanael KurcabPartner

Nathanael KurcabPartner Liv ChapAssociate

Liv ChapAssociate Nicholas W. KennedyAssociate

Nicholas W. KennedyAssociate Reiley Jo PorterAssociate

Reiley Jo PorterAssociate