Updates to Task Force Guidance | District Courts Follow Different Reasoning to Hold Executive Order 14042 Invalid: Circuit Courts to Determine Which Arguments Succeed or Fail

The fast and furious Jenga game over when and with which federal vaccine mandate a company must comply might finally have reached a turning point. On January 13, 2022, the Supreme Court issued dual per curiam opinions in which it blocked the Occupational Safety and Health Administration’s (“OSHA’s”) emergency temporary standards (“ETS”), otherwise known as the “vaccine or test” mandate, and lifted the injunction of the vaccine mandate issued by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (“CMS”), as further reported on in this client alert. Those decisions may signal an ominous fate for Executive Order 14042 (“EO” or “EO 14042”) and the federal contractor vaccine mandate, which has now shambled past the January 18, 2022 vaccination deadline. Nevertheless, contractors should continue to track developments in all major cases, particularly including the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit’s review of the nationwide preliminary injunction, as well as any case challenging the EO in the Supreme Court. This alert accordingly provides updates on the Safer Federal Workforce Task Force (“Task Force”) FAQs, five major cases in which district courts have issued preliminary injunctions, and key takeaways from the Supreme Court’s recent federal vaccine mandate opinions.

Updates to Testing and Vaccination Requirements

Shortly after our last alert, the Task Force published on its “For Federal Contractors” page a response to the multiple preliminary injunction orders. In short, “[t]he Government will take no action to enforce the clause implementing requirements of Executive Order 14042, absent further written notice from the agency, where the place of performance identified in the contract is in a U.S. state or outlying area subject to a court order prohibiting the application of requirements pursuant to the Executive Order.” In other words, the Federal Government will not enforce EO 14042 unless the applicable preliminary injunction(s) are overturned or the EO is upheld on the merits.

More recently, on January 11, 2022, the Task Force issued updates to its FAQs on “Testing” and “Vaccinations.” These updates indicate that agencies have until February 15, 2022, to establish COVID-19 screening testing programs, the purpose of which is to “help[] to identify unknown cases so that measures can be taken to prevent further transmission. Screening testing is separate and distinct from diagnostic testing, which should be performed on anyone that has signs and symptoms consistent with COVID-19 or following recent known or suspected exposure to SARS-CoV-2.” The following are a few key FAQ updates to which contractors should pay particular attention (emphases added):

Q: Should agencies establish a screening testing program for SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19?

A: Yes, agencies should establish a COVID-19 screening testing program by February 15, 2022 for employees who are not fully vaccinated, including due to a pending or approved request for exception or extension from the COVID-19 vaccination requirement for Federal employees. If an agency is engaged in enforcement steps with an employee covered by the vaccination requirement who is not fully vaccinated and who does not have a pending or approved exception or extension request, those employees should also be included in the agency’s screening testing program.

An agency generally does not need to include onsite contractor employees or fully vaccinated employees in its screening testing program. For certain roles, functions, or work environments, an agency may determine that it is necessary that certain onsite contractor employees, certain employees regardless of their vaccination status, or certain employees and certain onsite contractor employees regardless of their vaccination status must participate in screening testing, given operational or administrative considerations associated with conducting screening testing for those roles, functions, or work environments.

Q: Are Federal employees and contractor employees participating in an agency screening testing program limited in their ability to work onsite in between tests?

A: No, provided that they have met any applicable testing requirement and have not tested positive for COVID-19, Federal employees and contractor employees participating in an agency screening testing program are not limited in their ability to work onsite between tests, although they should comply with all relevant safety protocols. However, if the employee or contractor employee has come into close contact with a person with COVID-19 during this time, they should follow CDC guidelines for testing and quarantine, as well as any other requirements set forth in agency workplace safety protocols. Similarly, if they have symptoms consistent with COVID-19, they should follow agency protocols and not enter a worksite.

Agencies should develop a procedure for addressing circumstances in which employees or onsite contractor employees miss their required test, which may include restricting the individual’s access to worksites if they have not obtained a test within a period of time specified by the agency.

An employee’s failure to comply with testing requirements can result in disciplinary action, up to and including removal. An agency may separately elect to bar the employee from the agency workplace for the safety of others pending resolution of any disciplinary action. A contractor employee’s failure to comply with testing requirements may result in that individual being denied entry to a Federal facility. Such circumstances do not relieve the contractor from meeting all contractual requirements.

Q: Does the employee have a responsibility to pay for diagnostic testing if the exposure is not work-related?

A: An agency is not responsible for providing diagnostic testing to an individual as a result of a potential exposure that is not work-related. An employee or contractor employee who comes into close contact with a person with COVID-19 outside of work should follow CDC guidelines for testing and quarantine consistent with their vaccination status.

Although many of these FAQs merely confirm or expand upon information and agency policies that have essentially been in place for some time, contractors should carefully review all Task Force updates, agencies’ forthcoming COVID-19 “screening testing programs,” and updates to agency guidance, such as the multiple revised Department of Defense Health Protection Guidance memoranda.

Status of Preliminary Injunctions Currently In Effect

Over the past two months, district courts have separately issued five preliminary injunctions of EO 14042 and its implementing guidance. Those injunctions vary in both reasoning and scope, and the Federal Government has appealed all five orders. Although no circuit court has issued a decision on the merits of an appeal, both the Sixth and Eleventh Circuits have denied the Federal Government’s motions to stay the injunctions pending appeal. As a result, the nationwide preliminary injunction will remain in place for the foreseeable future, with oral argument in the Eleventh Circuit tentatively scheduled for the week of April 4, 2022. If, however, the district court grants the underlying requests in the Federal Government’s fully briefed motion to clarify the scope of the preliminary injunction, the Federal Government will be able to “enforce the COVID-19 safety clause’s requirements that do not relate to vaccination” and “reach agreements with federal contractors to abide by the COVID-19 safety clause, even if Defendants cannot enforce those agreements.”[1] Other State-filed suits seeking preliminary injunctions remain pending before the district courts, including Arizona (hearing pending), Texas (currently stayed), and Oklahoma (hearing pending).

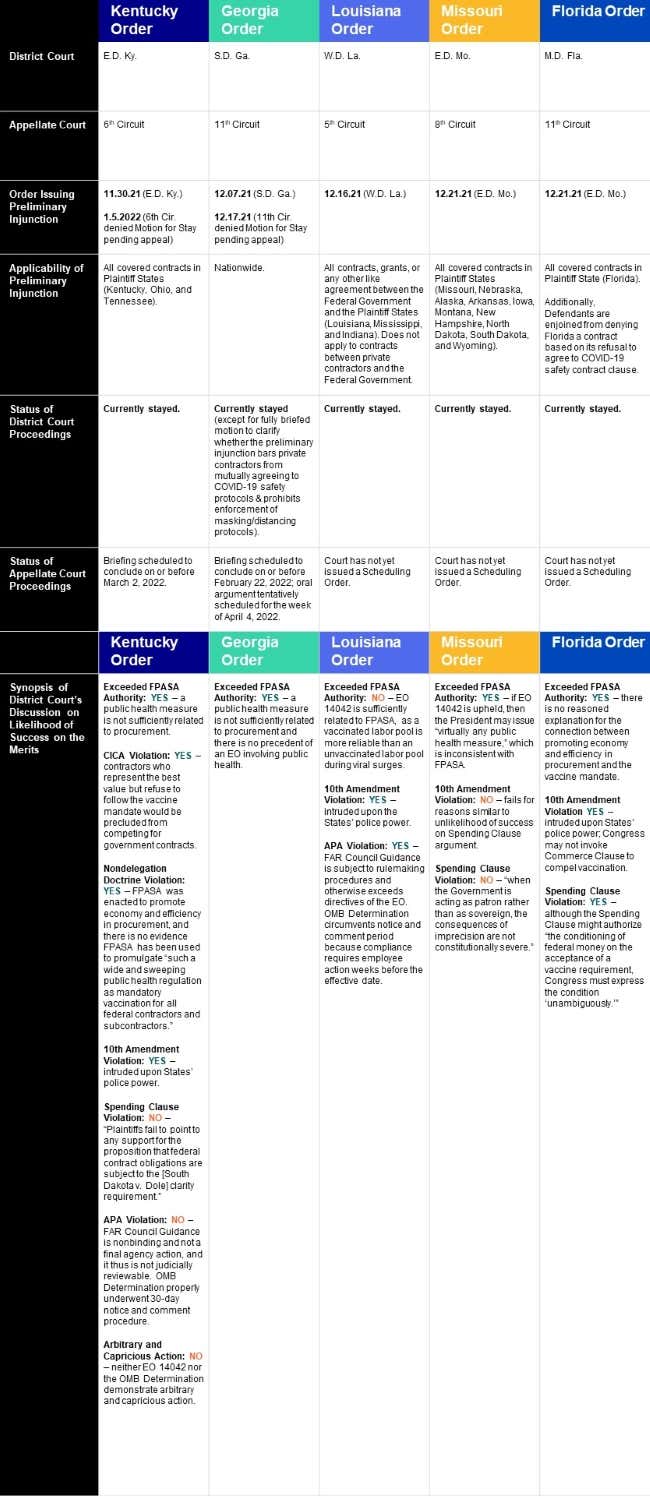

The below chart summarizes the status of all five preliminary injunctions, including key dates and the courts’ preliminary—but not determinative—findings on the merits. Notably, the courts have largely focused on whether the Federal Property and Administrative Services Act (“FPASA”) allows the President to issue a federal contractor vaccine mandate, with most courts finding that it does not.

Contractors should continue to closely monitor developments in these cases. In addition, contractors should keep a wary eye on the lawsuits challenging the OSHA and CMS (or U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (“HHS”)) mandates, given that the district court decisions blocking the federal contractor mandate all relied on the 5th Circuit’s decision in BST Holdings, LLC v. OSHA, which preliminarily enjoined OSHA’s ETS – a decision that the 6th Circuit overturned after hearing the consolidated cases but then was reversed by the Supreme Court.

Takeaways from the Supreme Court’s Recent Federal Vaccine Mandate Decisions

In addition to the preliminary district court findings, the Supreme Court’s per curiam opinions on the CMS and OSHA mandates suggest that EO 14042 and the federal contractor vaccine mandate will likely face an uphill battle. In both decisions, the Court provided a comprehensive analysis of whether the relevant statutes conferred upon the Secretaries of HHS (CMS rule) and the U.S. Department of Labor (OSHA ETS) the authority to promulgate the mandates, with a particular focus on both the text and history of applicable statutes and prior agency rulemaking practices. As several of the district courts have noted, EO 14042 is the first of its kind to rely upon FPASA when addressing government contractors and matters of public health, such as a vaccine mandate. The term “health” is also effectively absent from FPASA (see 40 U.S.C. §§ 101, et seq. ((Subtitle I, Chs. 1–13)). The majority, concurring, and dissenting opinions also addressed many principles at issue in the EO cases, including notice-and-comment procedures, States’ police powers, and separation of powers.

In a 5-4 decision to stay the dual preliminary injunctions of the CMS mandate, the Supreme Court found that the Secretary of HHS acted within his delegated authority based on the text of the applicable statutes. In reaching this conclusion, the majority also cited to the “longstanding practice” of HHS imposing requirements on healthcare facilities to comply with “a host of conditions that address the safe and effective provision of healthcare,” including hospital programs that “govern the ‘surveillance, prevention, and control of . . . infectious diseases.’” The Court further highlighted the Secretary’s routine imposition of eligibility and duty-related conditions on healthcare workers, pointing out that the CMS mandate does not cover staff who telework full-time and that it provides medical and religious exemptions. Last, the Court opined that the overwhelming support of the rule by healthcare workers and public health organizations connote the predictability of this type of health and safety regulation.

In a dissenting opinion, Justice Thomas disagreed that the Secretary had the authority to impose a vaccine mandate, finding that permissible “[r]ules carrying out the ‘administration’ of Medicare and Medicaid are those that serve ‘the practical management and direction’ of those programs,” not a rule that “compels millions of healthcare workers to undergo an unwanted medical procedure that ‘cannot be removed at the end of the shift.’” Particularly relevant to EO 14042, Justice Thomas argued that

[v]accine mandates also fall squarely within a State’s police power, and, until now, only rarely have been a tool of the Federal Government. If Congress had wanted to grant CMS authority to impose a nationwide vaccine mandate, and consequently alter the state‑federal balance, it would have said so clearly. It did not.

(Citations omitted).

In a separate dissenting opinion, Justice Alito largely took issue with the Secretary’s decision to forego the notice-and-comment process. Explaining that the Constitution vests the authority to enact federal laws in Congress, whose Members are elected by and are charged with listening to the people, Justice Alito criticized the emerging practice of federal law not being made by Congress and instead coming “in the form of rules issued by unelected administrators.” By preliminarily upholding the Secretary’s “extraordinary” departure from the ordinary notice-and-comment procedures, which he deemed improper, Justice Alito warned that the majority’s ruling “will ripple through administrative agencies’ future decisionmaking,” as it “shifts the presumption against compliance with procedural strictures from the unelected agency to the people they regulate.” Moreover, neither CMS nor the Court provided a limiting principle for how an agency can “regulate first and listen later,” irrespective of an “unexplained and unjustified delay.”

The Supreme Court’s treatment of the CMS mandate may provide some hint of EO 14042’s fate. Although EO 14042 provides certain accommodations, the Task Force guidance does not afford similar exceptions to covered employees who telework and imposes far-reaching vaccination requirements when non-covered employees who are not covered might come in contact with those who are. Additionally, much of the implementing guidance either did not involve a notice-and-comment process or underwent expedited processes, and the agencies likewise rolled out their class deviations on an accelerated basis that took effect before the promulgation of any formal regulations. These potential pitfalls of EO 14042, in addition to the text and history of FPASA, become even more pronounced when measured against the Court’s OSHA ETS opinion.

The Supreme Court’s 6-3 decision reinstating the stay of OSHA’s ETS similarly analyzed the text of the relevant statute but held that OSHA exceeded its delegated authority. Although the Court recognized OSHA is tasked with ensuring “safe and healthful” working conditions, it found that “such standards must be ‘reasonably necessary or appropriate to provide safe or healthful employment’” and be developed through notice-and-comment procedures. Taking exception through the use emergency temporary standards, the Court explained, is permitted “only in the narrowest of circumstances” – when necessary to protect employees from “grave danger from exposure to substances or agents determined to be toxic or physically harmful or from new hazards.” The Court determined that exception did not apply because the risk of contracting COVID-19 is a “universal risk . . . no different from the day-to-day dangers that all face from crime, air pollution, or any number of communicable diseases.”

The Court also took issue with the lack of historical precedent for OSHA issuing “a broad public health regulation of this kind,” which impacts 84 million Americans, provides “largely illusory” and narrow exemptions for employees who either telework or work exclusively outdoors, affords employers the discretion to permit weekly testing at the employees’ expense and time, imposes “hefty fines” for violations, and requires workers to wear masks every workday – mandates that OSHA and Congress have “never before imposed.” Nevertheless, the Court opined that OSHA can regulate occupation-specific risks related to COVID-19, provided such regulations are targeted to address special dangers the virus poses due to an employee’s job or workplace.

In a concurring opinion, Justice Gorsuch primarily focused on the States’ authority to regulate public health and on separation of powers principles. Regarding the latter, he emphasized the significance of the Major Questions Doctrine (related to the Nondelegation Doctrine), which protects against agency interpretations that implicate decisions of substantial economic and political significance. Where an administrative agency “seek[s] to regulate the daily lives and liberties of millions of Americans,” Justice Gorsuch explained, it “must at least be able to trace that power to a clear grant of authority from Congress,” which OSHA could not do.

Justice Breyer took essentially the opposite approach in a dissenting opinion joined by two other Justices. Unlike the majority, Justice Breyer concluded that “COVID-19, in short, is a menace in work settings,” and that “the administrative agency charged with ensuring health and safety in workplaces did what Congress commanded it to: It took action to address COVID-19’s continuing threat in those spaces.” He further explained that “OSHA’s rule perfectly fits” the standard for issuing emergency temporary standards, as the virus that causes COVID-19 is both a new hazard and physically harmful agent that poses a grave danger to millions of employees. Moreover, the ETS provide adequate exceptions and accommodations, permit a masking-or-testing policy, and are based on extensive studies and reports that confirm their effectiveness in limiting the threat of COVID-19 in most workplaces. He also found that OSHA has “long regulated risks that arise both inside and outside of the workplace,” including regulation of infectious disease and the facilitation of vaccines, and that just last year, Congress appropriated $100 million for OSHA “‘to carry out COVID-19 related worker protection activities’ in work environments of all kinds” through the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021.

Considering the balance of harms and public interest, Justice Breyer underscored the countervailing economic benefits and fewer employee absences due to illness that the ETS help provide. Citing record deaths and hospitalizations, he explained that “[f]ar from diminishing, the need for broadly applicable workplace protections remains strong, for all the many reasons OSHA gave.” Justice Breyer concluded by stressing the importance of deference to experts dealing with emergency conditions, criticizing the majority’s holding as one that “usurps a decision that rightfully belongs to others” and lacks a legal basis, because “[i]n the face of a still-raging pandemic, this Court tells the agency charged with protecting worker safety that it may not do so in all the workplaces needed.”

Unlike OSHA, the implementing agencies for EO 14042 and the FAR Council are not staffed with a wide array of health experts specifically charged with ensuring workplace safety. And although the Task Force is responsible for issuing guidance that interprets EO 14042, the goals of promoting economy and efficiency in procurement are arguably muddied by the expansive vaccine mandate that offers fewer exceptions than the OSHA ETS. Although these decisions do not necessarily dictate the fate of EO 14042 and its implementing guidance, the analysis in each signals that the more stringent federal contractor vaccine mandate faces a bumpy road ahead.

[1] Defs.’ Reply in Supp. of Req. for Clarification at 1, State of Georgia, et al. v. President of the United States, et al., No. 21-163 (S.D. Ga. Jan. 14, 2022), ECF No. 111.

- J. Alex WardPartner

- Krista A. NunezAssociate