2020 Poison Pill Recap and Current Trends

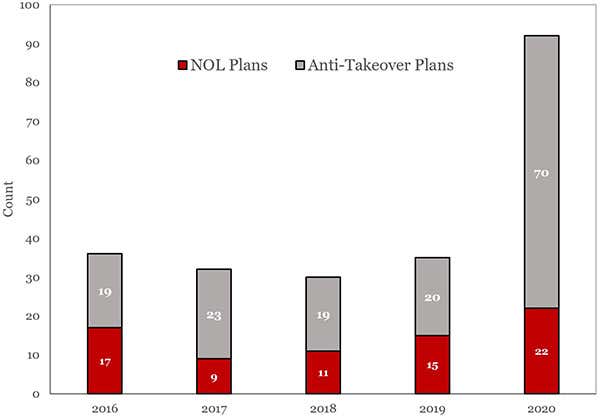

The number of stockholder rights plans (also known as “poison pills”) adopted in 2020 significantly increased compared to prior years.

The collapse in public company equity values during the inception of the COVID-19 pandemic made public companies more vulnerable to opportunistic acquisition and activist strategies. In response, many companies chose to implement rights plans as defensive measures, and many more boards did the work to prepare a plan so they could implement it quickly if needed (colloquially referred to as putting a plan “on the shelf”).

Under a rights plan, a company issues to its stockholders rights to purchase from the company newly issued shares of company stock. If someone acquires ownership above a specified threshold (typically 10% or 15%), the rights plan is triggered, and the stockholders (other than the triggering acquiror) can purchase shares at 50% of the market price. The board can also exchange the rights for shares of stock rather than allowing stockholders to exercise the rights. Either result significantly dilutes the triggering acquiror, thus discouraging—though not necessarily preventing—a person from exceeding that specified threshold without prior approval by the company’s board.

Last year saw about three times as many rights plans adopted compared to historical numbers.[1]

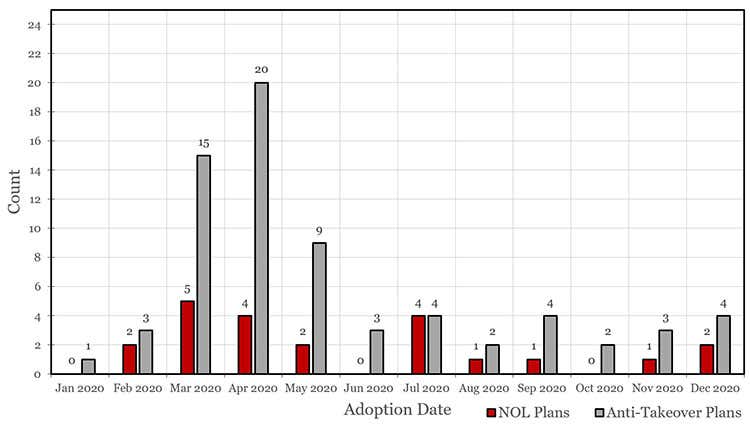

Most rights plans were put in place during the height of the market dislocation, with 60% being implemented during March, April and May.[2] However, as the markets normalized in the second half of 2020, and the risks related to opportunistic acquisition and activist strategies declined, the rate of adoptions slowed and fell in line with prior years—a trend we expect to continue in 2021.

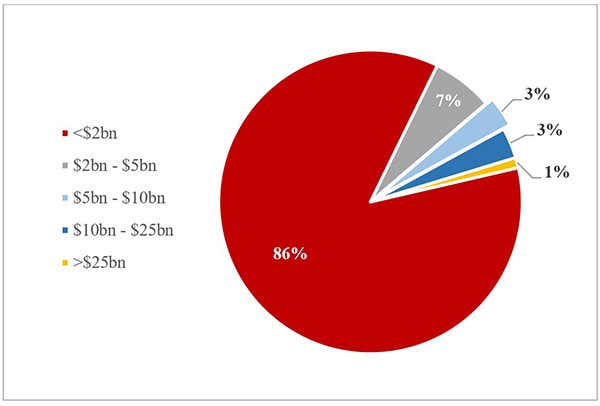

Rights plan adoptions were also largely concentrated in small cap companies with market capitalizations under $2 billion.[3] Small cap companies are particularly vulnerable to opportunistic acquisition and activist strategies because less capital is required to secure a meaningful ownership percentage, and the early warning system afforded by the premerger notification rules under the Hart-Scott-Rodino Antitrust Improvements Act of 1976[4] (triggered at $94 million in 2020 and $92 million in 2021) only become applicable at a much higher ownership percentage compared to larger companies.

In light of the resurgence in rights plan adoptions during 2020, we have prepared this article discussing some of the important and evolving features of rights plans and the various considerations that go along with them.

I. Triggering Percentage

Every rights plan sets a triggering percentage. If a stockholder acquires beneficial ownership[5] of a number of company common shares that exceeds the triggering percentage, the rights plan is triggered, and the acquiring stockholder’s ownership is significantly diluted.

Although the triggering percentage chosen will depend on a company’s specific situation and the threat being addressed, most anti-takeover rights plans have triggering percentages ranging from 10% to 20%.[6]

Below are some considerations that should be taken into account when setting the triggering percentage:

Percentage: Traditionally, the triggering percentage was set at 15% or 20% for all stockholders. This allowed stockholders flexibility to acquire a significant number of shares while limiting the risk of any stockholder or group of stockholders acquiring control. Notably, the 15% triggering percentage corresponds with the ownership percentage that would cause a stockholder to be an “interested stockholder” under Delaware’s anti-takeover statute (Section 203 of the Delaware General Corporation Law). This triggering percentage has been one of the most prevalent percentages in rights plans for decades on the basis that the Delaware legislature endorsed it as the ownership percentage that raises a threat sufficient to trigger the state anti-takeover statute.

More recently, however, many companies are setting the triggering percentage at 10%, particularly to address a threat posed by an activist investor. An activist investor will typically acquire a smaller stake in a company and then use that stake, on its own or with other activist investors, to push for major corporate change. Activists typically will not seek ownership percentages of 15% or more.

Bifurcated Triggers: Some rights plans bifurcate the trigger, setting a higher triggering percentage for passive investors[7] (e.g., Schedule 13G filers) and a lower, general triggering percentage. If the general triggering percentage is set below 15%, most recent plans bifurcate the trigger, with the higher triggering percentage typically being set at 20%. Delaware courts have approved bifurcated triggers in certain circumstances (see Third Point LLC v. Ruprecht,[8] where the rights plan imposed a 20% triggering percentage on passive investors and a 10% triggering percentage on others).

Although less common, instead of setting a triggering percentage for passive investors, some plans exempt them from the rights plan altogether as long as they remain passive. In this case, the definition of passive investor will typically be narrower and limited to persons that have filed a Schedule 13G pursuant to the requirements of Rule 13d-1(b) (i.e., a “qualified institutional investor”) or Rule 13d-1(c) (i.e., a “passive investor” that is not a beneficial owner of 20% or more of the issuer’s shares). Given these requirements, this exemption results in qualified institutional investors having no triggering percentage and other passive investors having a 20% triggering percentage.

Of the 70 non-NOL rights plans adopted in 2020, more than half bifurcated the triggering percentage.[9]

Tailored to Specific Threat: When setting the triggering percentage, the company should consider the specific threat being addressed by the rights plan.

For example, if the company is facing a hostile takeover, a rights plan with a triggering percentage of 15% or 20% may be appropriate, as the acquiror’s objective would typically be to buy 100% of the company or, at least, a controlling interest. In this case, a higher triggering percentage will still serve the rights plan’s purpose by forcing the strategic acquiror to negotiate with the board (unless the acquiror is successful in conducting a proxy contest to replace the board).

However, if the company is facing a threat by an activist investor, a rights plan with a bifurcated trigger of 10% in general and 20% for passive investors may make sense because activist investors often try to exert influence on a company through smaller stakes and are not necessarily seeking ownership of a large block.

- Lower Percentage; More Scrutiny. The lower the company sets the rights plan’s triggering percentage, the more susceptible it is to scrutiny.[10] For example, after The Williams Companies adopted a rights plan (which was not an NOL plan) with a 5% triggering percentage, ISS recommended voting “against” the company’s board chair and “cautionary support” for all of its other directors, finding the 5% triggering percentage as “highly restrictive.”[11] About 1/3 of the shares that were voted at the company’s annual meeting were voted against the chair. In addition, certain of The Williams Companies stockholders (none of which are an activist investor or hostile acquiror) filed a lawsuit (see Section III) challenging the rights plan, claiming that the 5% triggering percentage was “stunningly low” and “undermine[d] the stockholder franchise.” The case is awaiting decision after a January 2021 trial.

II. The Inadvertent Triggering Exception

Traditionally, a rights plan was crafted as a trip wire: if an acquiror crosses the triggering percentage, the rights plan is triggered and the dilutive effects cannot be stopped or reversed. Not even the company’s board can undo them.

Crafting a rights plan as a trip wire creates a strong deterrent to an acquiror thinking about a hostile takeover or accumulating a control position in a company without obtaining the board’s prior approval—the acquiror will know that it cannot force or persuade the board after the fact into providing an exception since that is not permitted by the plan. This deterrent effect forces the acquiror to seek the board’s prior approval, thereby giving the board leverage in negotiations.

But crafting a rights plan as a trip wire can also lead to a bad result for the company if an acquiror that has no intention of buying control or influencing the company crosses the triggering percentage inadvertently. This is so because, when a rights plan is triggered, it not only dilutes the acquiring person but also causes a major change in the capital structure of the company (with the company issuing a number of new shares equal to almost its current capitalization to many multiples of its current capitalization), requires the execution of complex mechanics relating to the exercise or exchange of the rights and significantly distracts the company’s board and its management from the company’s core operations. These consequences can create a major headache for a company and may interrupt trading of the company’s securities[12]—and unnecessarily so where an acquiror crosses the triggering percentage due to a legitimate accident.

To avoid the consequences of inadvertent triggering, almost every rights plan includes a carve-out provision for acquirors who inadvertently trigger (as determined by the board) the plan.

How can a stockholder accidentally exceed the triggering percentage? Companies publicize their rights plans. Buyers of shares of public companies at these levels of ownership should be aware of numerous hurdles, such as U.S. federal securities law beneficial ownership reporting requirements triggered at 5% or 10% beneficial ownership (under Sections 13(d) and 16 of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, as amended (the “Exchange Act”)) and antitrust and other regulatory thresholds, as well as rights plans themselves. But, surprisingly, it does happen.[13] A buyer might have established an automated purchase program without appropriate controls. Another scenario would be a fund complex with multiple portfolio managers and inadequate enterprise-level controls, such that multiple portfolio managers purchase shares of the same company, each below the triggering percentage but in the aggregate above the threshold. Another scenario would result from a merger or acquisition, where both parties to the transaction own shares of a third company and, following the closing of the transaction, the combined company winds up owning both blocks of shares, together exceeding the triggering percentage.

Inadvertent triggering is more likely in the case of rights plans with lower triggering percentages; an investor is significantly more likely to accidentally cross a 5% threshold than a 15% threshold. The carve-out provision therefore will be more relevant in rights plans with a lower threshold.

A standard carve-out provision for inadvertent triggering looks like the following:

If the Board determines that a person who would otherwise be an Acquiring Person has become such inadvertently (including because such person was unaware that it Beneficially Owned a percentage of the Common Shares that would otherwise cause such Person to be an Acquiring Person or such Person was aware of the extent of the Common Shares that it Beneficially Owned but had no actual knowledge of the consequences of such Beneficial Ownership), and such Person divests as promptly as practicable (as determined by the Board) a sufficient number of Common Shares so that such Person would no longer be an Acquiring Person, then such Person shall not be deemed to be an Acquiring Person.

Companies may include a few bells and whistles on this standard carve-out provision, some of the most prevalent being:

- No intention to influence company: Some rights plans provide that the provision only applies if the board also determines that the acquiror went over the triggering percentage without intending to obtain, change or influence control of the company.

- Concurrence of board members not affiliated with acquiror: Rights plans sometimes include a provision requiring that the determination of the board include the concurrence of a majority of the members of the board who are not, and are not representatives, nominees, affiliates or associates of, the acquiror that crossed the triggering percentage.

- Opportunity to divest shares: Rights plans also can allow an acquiror that crosses the triggering percentage inadvertently to enter into an irrevocable commitment, satisfactory to the board, to divest the necessary shares within a certain period of time instead of forcing the acquiror to sell down immediately.

In addition to the standard carve-out provision, companies generally include a related provision that a stockholder cannot become a triggering acquiror solely as the result of the company repurchasing its outstanding shares. A share repurchase by the company reduces the number of outstanding shares and thus increases the proportional number of shares beneficially owned by the stockholder. This repurchase could lead to a form of “inadvertent” triggering of a rights plan by the stockholder, as the stockholder could cross the triggering percentage, having taken no action to increase its ownership.

Ultimately, a rights plan should be drafted with enough flexibility that the board can address inadvertent triggers, but not so much flexibility that the deterrent effect is reduced or that the board has too much of a burden to determine whether the rights plan has been triggered.

III. Acting in Concert

Rights plans traditionally have been drafted to apply the ownership threshold to the aggregated ownership of certain groups of stockholders. Specifically, the definition of beneficial ownership in most rights plans has included not only beneficial ownership as defined for purposes of Regulation 13D under the Exchange Act but also securities that are subject to any agreement, arrangement or understanding for the purpose of acquiring, holding, voting or disposing of a company’s securities.[14]

Over the years, especially the past decade, however, increased investor activism (particularly hedge fund activism) has given rise to stockholders coordinating their activities in ways not captured by the traditional definition of beneficial ownership. A chief example of this is hedge funds with small stakes in companies (i.e., less than 5%) coordinating in a way that aggregates to a large block of stock that allows them greater leverage to influence management. Hedge funds with the same or a similar (often short-term) objective may form a loose network and communicate informally. When they act in concert or in parallel to effect change at a company, they may do so without any formal or even tacit agreements. Because there is no actual agreement, arrangement or understanding, the traditional definition of beneficial ownership will not always capture their coordination.

To protect against this type of stockholder activity, some companies have included “acting in concert” provisions in their rights plans that broaden the traditional definition of beneficial ownership to capture certain kinds of informal coordination among stockholders. Two types of acting in concert provisions have emerged: (1) an express provision and (2) a general provision.

Express provision: Under an express provision, a person is deemed to beneficially own any shares that are beneficially owned by any other person with respect to which such person is “Acting in Concert.”

“Acting in Concert” then is defined to provide, with some potential variations, that a person will be deemed to be “Acting in Concert” with another person if such person knowingly acts (whether or not pursuant to an express agreement, arrangement or understanding) at any time after the first public announcement of the adoption of the rights plan, in concert or in parallel with such other person, or towards a common goal with such other person, relating to changing or influencing the control of the company or in connection with or as a participant in any transaction having that purpose or effect, where:

(i) each person is conscious of the other person’s conduct, and this awareness is an element in their respective decision-making processes; and

(ii) at least one additional factor supports a determination by the board that such persons intended to act in concert or in parallel, which additional factors may include exchanging information, attending meetings, conducting discussions, or making or soliciting invitations to act in concert or in parallel; provided that the additional factor required shall not include actions by an officer or director of the company acting in such capacities.

The defined term also makes clear that a person is not “Acting In Concert” with another person as a result of (a) making or receiving revocable proxies given in response to a public solicitation made to more than ten stockholders of the company pursuant to the Exchange Act or (b) soliciting or being solicited in connection with a public tender or exchange offer made pursuant to the Exchange Act.

- General Provision: A rights plan alternatively may provide that a person is deemed to beneficially own any shares which are beneficially owned by any other person with which the first person has any agreement, arrangement or understanding (whether or not in writing) to cooperate in obtaining, changing or influencing control of the company.

Not all rights plans include an acting in concert provision (for plans adopted in 2020, about half had them).[15]

When companies are considering whether to add an acting in concert provision, they should be aware that, while Delaware courts have generally upheld the use of the traditional definition of beneficial ownership in rights plans,[16] the courts have not expressly ruled on triggering percentages that use an acting in concert provision.

In addition, some stockholders have criticized acting in concert provisions as chilling their ability to communicate with other stockholders. For example:

- In the 2017 dispute between Carl Icahn and Sandridge Energy, Icahn criticized an express acting in concert provision as “patently absurd” and “a transparent attempt to preclude large shareholders from communicating with one another and exercising their rights as shareholders.”[17] Sandridge later deleted the acting in concert provision in order to “ensure there is no unintended consequence that might discourage communications between shareholders . . . .”[18]

- In the 2018 dispute between John Schnatter and Papa John’s, Schnatter criticized an express acting in concert provision, alleging that it prevented him from communicating with other stockholders regarding corporate matters such as opposition to board proposals.[19]

- In August 2020, three lawsuits[20] were filed by the same plaintiffs’ law firm challenging the express acting in concert provision in three rights plans adopted during the pandemic downturn, each claiming that the provision “shut[s] down the ability of any stockholder or group of shareholders to seek to influence the direction of the Company.” As of this writing, one lawsuit is awaiting action following post-trial briefing, one is awaiting settlement-related discovery, and a stipulation of settlement was recently filed in the third lawsuit in which the parties have agreed to, among other things, amend the express acting in concert provision to be a general acting in concert provision.[21]

Ultimately, companies should consider the facts and circumstances—particularly any actual threats faced—when determining whether to add an acting in concert provision to their rights plans. For instance, if a rights plan is being adopted in response to an actual hostile takeover launched by a strategic acquiror, an acting in concert provision may be unnecessary and may create needless enforceability concerns; however, if a rights plan is being adopted in response to an activist investor, particularly one with a history of acting in parallel with other activist investors, an acting in concert provision may be warranted.

IV. Grandfathering Existing Stockholders

Rights plans commonly include a “grandfather clause” that exempts stockholders who, at the time of the rights plan’s adoption, have ownership stakes equal to or greater than the rights plan’s triggering percentage. This allows these stockholders to maintain their stakes without immediately triggering the rights plan upon adoption.

Not every company needs a grandfather clause—i.e., if it has no stockholders above the rights plan’s triggering percentage. However, it has become customary to include a grandfather clause as a precaution, even where there is no known stockholder at or above the triggering percentage, to avoid triggering the rights plan upon adoption if a stockholder has a greater interest than known to the board, particularly given the broad scope of “beneficial ownership” covered by rights plans, which goes beyond that covered by federal securities rules and reported by investors in their public filings. To be sure, the lower the triggering percentage, the greater the chances that there is an unknown stockholder with a larger ownership interest.

A typical grandfather clause is drafted as follows: “No Person who Beneficially Owns, as of the time of the first public announcement of the declaration of the Rights dividend, 15% or more of the Common Shares then outstanding shall become an ‘Acquiring Person.’” This clause would also provide that grandfathered stockholders would no longer be exempt if they drop below the triggering percentage, meaning that if they again went above the relevant threshold, they would trigger the rights plan.

Below are some considerations that should be taken into account when including a grandfather clause:

- Should grandfathered stockholders be permitted to acquire additional shares up to a cap (e.g., an additional 1% of the shares outstanding)? Or, should they be prohibited from acquiring any additional shares?

- If there is a known stockholder with a large ownership stake, should a specific provision be drafted dedicated to the stockholder instead of relying on the general grandfather clause?

- If a large stockholder is being grandfathered (particularly an insider), to what extent should the company take that into account when setting the general triggering threshold?

How should founding stockholders and their families be handled?

For example, when considering a family that owns a significant number of shares, some rights plans provide that individual family members are not deemed to beneficially own shares held by his or her family members. Depending on the circumstances, this language may result in each family member having an ownership stake below the triggering percentage and may allow each of them to acquire additional shares up to that threshold.

Other rights plans will aggregate the entire family ownership and place a higher cap on their aggregate ownership, whether it be their aggregate ownership at the time of the rights plan’s adoption or a higher threshold, so that family members can act collectively and transfer shares amongst each other if desired. Given the coverage of most rights plans of “arrangements and understandings,” as well as more formal agreements, care should be taken not to set too narrow a grandfather clause that is triggered right away.

- If, at the time of a rights plan’s adoption, a grandfathered stockholder is party to an agreement or arrangement (e.g., an option or other derivative contract) pursuant to which the stockholder is deemed the beneficial owner of common shares, should the stockholder be able to extend or exercise such arrangement when it expires? Or, should any extension or change in form of the ownership (e.g., exercise of the option to acquire actual ownership of shares) be considered an acquisition of additional common shares that would cause the rights plan to be triggered? To what extent can or should the company try to prevent such further acquisitions of shares based on existing arrangements?

Boards should try to understand who their significant stockholders are and the implications of grandfathering those stockholders when they prepare a rights plan for adoption, particularly in light of the speed with which shares may change hands.

For example, in 2014, American Apparel adopted a rights plan the day after its former CEO disclosed a 27% ownership stake.[22] However, before the plan was adopted, the former CEO had increased his stake to 43% by acquiring a significant block of shares from a hedge fund, and that large stake was grandfathered.

To help avoid situations like this one, companies should employ a good stock watch program to keep abreast of any unusual accumulations of its stock and hedge fund trading. It should also pay attention to rumors in the market.

Ultimately, the specifics of a grandfather clause will depend on facts and circumstances and should reflect, among other things, the company’s stockholder base, the identity and motives of any grandfathered stockholders, and the company’s relationship with any grandfathered stockholders.

V. Last Look

As discussed above, rights plans traditionally were crafted mostly as a trip wire: if an acquiror[23] exceeds the triggering percentage, the rights plan is automatically triggered without any additional action, and the dilutive effects cannot be stopped or reversed.

That said, an increasing proportion of rights plans provide the board a limited window after an acquiror exceeds the triggering percentage—typically 10 business days—during which the board can redeem for a nominal amount or otherwise terminate the rights. This is known as a “last look” provision, and it gives the board the ability to avoid the dilutive effects of a triggered rights plan.

About half of the rights plans adopted in 2020 contained a last look provision.[24]

A last look provision is typically drafted as follows:

The board may, at its option, at any time prior to the earlier of (i) the Distribution Date and (ii) the Expiration Date, redeem all, but not less than all, of the then outstanding rights at a redemption price of $0.0001 per right.

The “Distribution Date” is generally defined as the 10th day after the public announcement that a person has surpassed the triggering percentage, thus creating the 10-day window during which the board may redeem the rights under the triggered plan.[25] The board’s otherwise broad right to amend the plan (which would include the right to accelerate the expiration of the plan) generally becomes significantly limited at the same time as the redemption right expires.

In contrast, a trip-wire provision would provide that the board’s right to redeem the rights terminates when a person has surpassed the triggering percentage, rather than the occurrence of the Distribution Date.

There is some debate as to whether including a last look provision in a rights plan is good for the company. When a rights plan is crafted as a trip wire, the acquiror decides if the dilutive effects occur—it is the one that chooses to surpass the triggering percentage and thereby irreversibly trigger the plan.[26] But when a rights plan contains a last look provision, it is the company’s board that has the final call on whether the dilutive effects occur because it has 10 days to redeem the rights after the plan has been triggered.

On the one hand, it seems sensible to put this decision in the hands of the board rather than a third party. A triggered rights plan will significantly affect the company and its capital structure, with related distractions, as described above with respect to the inadvertent triggering exception, and events significantly affecting the company should be decided by the board.

On the other hand, giving the board the final call on whether the dilutive effects occur may weaken the rights plan’s deterrent value. This happens because, during the 10-day window after the plan has been triggered, the board will be under considerable pressure in deciding whether to redeem the rights. The pressure comes from the fact that the board’s decision must be made consistent with the board’s fiduciary duties, based on current knowledge of the company’s situation, including the “threat” posed by the particular acquiror and the potentially significant effects of the triggered plan on the company.

Pressure may also come from the company’s other stockholders. Although diluting the acquiror gives the other stockholders the chance to increase their ownership percentages at a deeply discounted value, or even for free (if the board opts to implement an exchange rather than to allow exercise of the rights), it will likely take the acquiror’s proposed deal off the table. Moreover, at the point when a plan is triggered, at least in the takeover context, a significant number of the company’s stockholders may be arbitragers who had bought company stock with the expectation that a deal would happen and will likely want the board to redeem the rights and let the acquisition proceed, with less interest in the company’s long-term prospects.

As a result, if a rights plan with a last look provision is triggered, the acquiror knows that the board may be incentivized to negotiate and that there is a possibility that the board will decide to redeem or terminate the rights—thereby reducing the rights plan’s deterrent value.

In the end, whether or not to include a last look provision is an important issue for the board to consider, and it is key that the board be advised as to the positives and negatives of including the provision.

VI. Qualifying Offer

Some rights plans contain what is known as a “qualifying offer” provision.[27] This provision provides that, if an offer meets certain defined criteria, and the board does not redeem the rights or exempt the offer within a certain period of time, the stockholders have the right to force the board to call a special stockholder meeting to vote on whether to exempt the offer from the rights plan.[28]

Most rights plans do not include a qualifying offer provision. Indeed, only about 15% of the rights plans adopted in 2020 contained the provision.[29] A board contemplating a qualifying offer provision should consider whether the provision could, under the circumstances, reduce the board’s leverage by opening a path for an acquiror to sidestep the board and appeal directly to stockholders, whether it could hinder the board’s ability to run an orderly auction process or whether it could allow stockholders to vote—in what is essentially a referendum on the offer—where the acquiror would not have otherwise had the ability to tangibly demonstrate wide stockholder support.[30]

That said, some boards have determined to include the provision to emphasize to stockholders that they are not categorically opposed to a takeover of the company. In fact, both ISS and Glass Lewis state in their guidance for stockholder vote recommendations that rights plans should contain a qualifying offer provision.[31]

Although the specifics vary by rights plan, the following are the typical criteria that an offer would need to satisfy in order to be a “qualifying offer”:

- the offer is for cash, on a fully financed basis,[32] or for common stock of the offeror (or a combination of both), for all of the outstanding common stock of the company at the same per share consideration;

- the offer price exceeds (in some plans, by a minimum specified margin) the highest market price for the shares measured over a specified period of time prior to the commencement of the offer;

- the offer is conditioned on a minimum tender of at least a majority of each of (1) the common shares then outstanding and (2) the common shares then outstanding not held by the offeror;

- the offer is subject only to the minimum tender condition and other customary conditions (and not conditions such as financing or offeror’s receipt of satisfactory rights to conduct due diligence on the company);

- the offer will remain open for a specified period of time after any special stockholder meeting that was requested by the stockholders with respect to the offer;

- the offeror commits to consummate a second-step merger as soon as possible after completion of the offer in which all shares not tendered in the offer will receive the same consideration paid pursuant to the offer; and

- if the offer includes common stock of the offeror, (1) the offeror is listed on NASDAQ or the NYSE, (2) no stockholder approval of the offeror is required and (3) no person owns more than 20% of the voting stock of the offeror.

Often, the rights plan provides that the company’s board (whether the whole board or a majority of the independent directors) determines whether an offer meets the defined criteria. Some rights plans, however, do not require such a determination by the board.

If an offer meets the defined criteria (i.e., it is a qualifying offer), and the board has not redeemed the rights or exempted the offer from the rights plan within a certain number of days after the offer has commenced, stockholders holding a specified percentage of the outstanding shares (excluding shares owned by the offeror) may submit a written demand to the board, directing the board to call a special stockholder meeting to vote on exempting the offer from the rights plan. After receiving such a demand, the board must convene the special meeting within a certain number of days. If the board fails to convene the special meeting, or holds the meeting and a majority of the outstanding shares (excluding shares held by the offeror) are voted in favor of exempting the offer from the rights plan at the meeting, the offer is deemed exempted from the rights plan, and the consummation of the offer will not trigger the rights plan.

Below are some of the key items to be considered when including a qualifying offer provision in a rights plan:

- What percentage of shares is necessary to cause the board to call the special stockholder meeting for consideration of the qualifying offer? The range varies, but is typically between 10% and 25%.

- How much time should the board be given to consider whether to redeem the rights or exempt the qualifying offer before the stockholder right to demand a stockholder meeting arises? Many qualifying offer provisions provide for 60-90 days.

- If a special stockholder meeting is demanded by the holders of the requisite number of shares, how long does the board have to call the meeting? The typical range is 90-120 days after receipt of the demand.

- What should the measurement period be for determining the “highest market price” for the company’s shares? Many qualifying offer provisions provide for 12 or 24 months prior to the commencement of the offer.

- Must the offer price represent a reasonable premium over the highest market price for the shares during the measuring period (which suggests that the offer price needs to be meaningfully greater than the highest market price)? Or, does the offer price only have to be greater than the highest market price?

- Should the offer not qualify as a “qualifying offer” if a financial advisor retained by the board renders an opinion that the consideration being offered to the stockholders is unfair or inadequate?

- If all or part of the proposed consideration is in the offeror’s stock, should the company have due diligence rights to investigate the offeror?

- Should each of the stockholders demanding the special meeting be required to satisfy the stockholder information requirements under the company’s advance notice bylaw?

In the end, a board contemplating a qualifying offer provision should consider the message it is trying to send to stockholders and any potential acquirors, and how the provision may play out under different circumstances in the future.

VII. Expiration of rights

Most rights plans provide that the rights expire 364 days after the adoption of the rights plan. This time period is largely chosen to fit within ISS and Glass Lewis guidance. Indeed, if a company adopts a rights plan without stockholder approval, the general policy of ISS is to recommend that stockholders vote against or withhold votes on all directors (other than new nominees), although ISS will consider votes on a case-by-case basis if the rights plan has a term of one year or less, depending on the disclosed rationale for the adoption and other factors. Glass Lewis has a similar policy.

When rights expire, companies have taken varying approaches regarding the expiration, including:

- Filing an amended Form 8-A with the Securities and Exchange Commission (the initial Form 8-A registered the rights under Section 12(b) of the Exchange Act), specifying that the rights have expired.

- Filing with Delaware a Certificate of Elimination with respect to the Certificate of Designation for the series of preferred stock that was to be issued upon exercise or exchange of the rights. The Certificate of Elimination eliminates the shares of this series of preferred stock and returns them to the status of authorized but unissued shares of preferred stock. If the company files a Certificate of Elimination, it would also need to file a Form 8-K with respect to the Certificate of Elimination.

- Issuing a press release announcing that the rights have expired. If the company issues a press release, it would also file a Form 8-K regarding the press release.

- Doing nothing—no filing of a Certificate of Elimination, issuing of a press release or amending the Form 8-A.

Notwithstanding the fact that most rights plans have a short duration of 364 days, some companies may determine that it is in the best interest of the company and its stockholders to accelerate expiration of the rights.[33] For example, the expiration date in five of the rights plans adopted in 2020 was accelerated.[34] There are numerous reasons for accelerating the expiration, including for purposes of settling with a stockholder, the circumstances which necessitated the adoption of the rights plan no longer exist (e.g., the company is no longer the subject of a hostile tender offer), and reinforcing the message that the board is following through on its word that the rights plan was adopted to protect stockholder value in light of the price and volatility issue that arose at the outset of the pandemic and not to entrench the board or management.

In recent years, very few companies have extended or replaced expiring rights plans. A company may believe that the original threat has subsided and that no other active threat warrants maintaining a plan in place. Letting the plan expire also is consistent with the positions of ISS and Glass Lewis, as noted above, who generally will recommend voting against directors who approve a rights plan with a term longer than a year that has not otherwise been voted on by the stockholders. Of the few companies that have renewed their rights plans, several have put that renewal to a stockholder vote. Of course, a company that lets its rights plan expire generally would be able to implement another rights plan if a new threat emerges, provided it has not imposed any restrictions on itself, and may wish to keep a plan “on the shelf” so it can move quickly in that regard. In any event, any decision to extend or replace a rights plan would be subject to the board’s fiduciary duties as if a new rights plan was being adopted.

Ultimately, the board will need to consider the best course of action for the company when the rights expire, including whether it should accelerate the expiration or even renew the plan.

VIII. Conclusion

Fundamentally, the 2020 surge in rights plan adoptions was primarily due to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and the resulting market dislocation. With markets returning to “normal,” a similar number of adoptions should not be expected for 2021 unless further disruption occurs, and we believe 2021 adoptions will be in line with historical figures. That being said, as the rights plans adopted in March, April and May of 2020 begin to expire over the course of the next three months, it will be interesting to see how companies react in the event of a big uptick in hostile M&A and activism.

*Law Clerk Miles Gilhuly contributed to this client alert.

[1] Deal Point Data.

[2] Deal Point Data.

[3] Deal Point Data.

[4] Under the HSR Act, unless an exemption applies, premerger notification is required where (1) as a result of a transaction, the acquiring person would hold voting securities of an issuer valued at more than $92 million, and the acquiring and acquired persons have total assets or annual net sales of at least $184 million and $18.4 million, respectively, or (2) the transaction is valued at more than $368 million. Premerger notification filings are not public; however, for most transactions, the acquiror must notify the issuer of the transaction and its potential HSR filing obligation. Thus, the issuer becomes aware of the intended stock accumulation (and hence the early warning system). In addition, the acquiror must observe a 30-day waiting period (15 days for cash tender offers) prior to completing the transaction, meaning it cannot purchase any additional issuer stock that would cross an HSR threshold and trigger a filing during that period.

[5] Beneficial ownership is defined in the rights plan, typically including, first, “beneficial ownership” within the meaning of Rule 13d-3 of the Exchange Act. This covers securities over which a person has or shares voting power or investment power, which includes the right to dispose, whether pursuant to any agreement, arrangement, understanding, relationship or otherwise. A rights plan typically expands the Exchange Act definition by including securities subject to such powers even if subject to certain conditions. The definition often also includes (i) securities underlying derivative contracts beneficially owned by a counterparty and (ii) securities owned by persons who have an agreement, arrangement or understanding for the purpose of acquiring, holding, voting or disposing of such securities. As discussed in Section III, recent rights plans also often include securities owned by other persons who have an agreement, arrangement or understanding for obtaining, changing or influencing control of the issuer.

In addition, the definition of beneficial ownership in most rights plans also borrows the definitions of “associates” and “affiliates” from the Exchange Act, expanding the securities deemed to be beneficially owned by a stockholder to include those deemed to be beneficially owned by “associates” or “affiliates” of the stockholder, which are defined under Rule 12b-2 of the Exchange Act as follows:

- an “associate” of a company’s stockholder is (1) any corporation or organization (other than the company or any of its majority-owned subsidiaries) of which the stockholder is an officer or partner or is, directly or indirectly, the beneficial owner of ten percent or more of any class of equity securities, (2) any trust or other estate in which the stockholder has a substantial beneficial interest or as to which the stockholder serves as trustee or in a similar fiduciary capacity, and (3) any relative or spouse of the stockholder, or any relative of the spouse, who has the same home as the stockholder or who is a director or officer of the company or any of the company’s parents or subsidiaries; and

- an “affiliate” of a stockholder is a person that controls, is controlled by, or is under common control with, the stockholder, whether directly or indirectly through one or more intermediaries.

[6] Rights plans designed to protect a company’s ability to use net operating losses (“NOLs”) will have a triggering percentage of 4.9%. The triggering percentage is set at this lower level because a company’s ability to use its NOLs will be negatively affected if it undergoes an “ownership change,” which occurs when the percentage of its stock owned by one or more stockholders who directly or indirectly owns more than 5% of the company’s stock increases by more than 50% within a 3-year period.

[7] Typically, a “passive investor” or “passive institutional investor” is defined as a stockholder who reported or is required to report its beneficial ownership of a company on Schedule 13G under the Exchange Act, but only so long as the stockholder (i) is eligible to report such ownership on Schedule 13G and (ii) has not reported and is not required to report such ownership on Schedule 13D. If, at any time, a passive investor no longer qualifies as such, the formerly passive investor will need to quickly sell down its stake below the general triggering percentage (typically within 10 days of no longer qualifying as a passive investor). Otherwise, the formerly passive investor will become an acquiring person under the rights plan.

[8] C.A. No. 9469-VCP (Del. Ch. May 2, 2014).

[9] Deal Point Data.

[10] Some states other than Delaware have enacted rights plan endorsement statutes. These statutes give the board wide latitude in selecting the plan’s terms, including the triggering percentage.

[11] Glass Lewis did not recommend voting against The Williams Companies’ directors.

[12] See Selectica, Inc. v. Versata Enterprises, Inc., C.A. No. 4241-VCN, 2010 WL 703062 (Del. Ch. Feb. 26, 2010).

[13] Instances of acquirors inadvertently triggering rights plans do not always become public. Below are two publicly known examples:

- In 1998, Crabbe Huson Group, Inc. inadvertently triggered Arcadia Financial Ltd.’s rights plan, acquiring 16.8% of Arcadia’s outstanding shares, which pushed it past the 15% threshold of Arcadia’s rights plan. See Tim Huber, Gulp! Buying spree triggers poison pill, Minneapolis/St. Paul Business Journal (February 8, 1998), available at: https://www.bizjournals.com/twincities/stories/1998/02/09/story2.html.

- In 2003, Scott Sacane, a Connecticut money manager, inadvertently triggered both Esperion Therapeutics’s and Aksys Ltd.’s rights plans, claiming that there was “a breakdown of internal controls” at the stockholder’s capital management company. See Floyd Norris, Market Place; Investor Says He Bought Stock and Didn't Know It, The New York Times (July 30, 2003), available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2003/07/30/business/market-place-investor-says-he-bought-stock-and-didn-t-know-it.html.

[14] Rights plans typically exclude from the definition of beneficial ownership a right to vote that arises from a revocable proxy given in response to a public solicitation made pursuant to the Exchange Act.

[15] Deal Point Data; this statistic excludes NOL rights plans.

[16] E.g., see Stahl v. Apple Bancorp, Inc., C.A. No. 11510, 1990 WL 114222 (Del. Ch. Aug. 9, 1990).

[17] See Carl Icahn, Letter to the Board of Directors of Sandridge Energy (Nov. 30, 2017), available at https://carlicahn.com/letter-to-the-board-of-directors-of-sandridge-energy/.

[18] See Sandridge, Letter to Shareholders (Jan. 23, 2018), available at https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/1349436/000119312518017581/d511604dex991.html.

[19] See Verified Complaint, Schnatter v. Shapiro, C.A. No. 2018-0646-AGB (Del. Ch.), filed Sept. 5, 2018.

[20] See Verified Complaint, Wolosky v. Armstrong, C.A. No. 2020-0707-KSJM (Del. Ch.), filed Aug. 27, 2020; Verified Complaint, Vladimir Gusinsky Revocable Trust v. Anderson, C.A. No. 2020-0714-KSJM (Del. Ch.), filed Aug 28, 2020; and Verified Complaint, Vladimir Gusinsky Revocable Trust v. Crenshaw, C.A. No. 2020-0716-KSJM (Del. Ch.), filed Aug 28, 2020.

[21] See Jeff Montgomery, Tribune Publishing, Class Near Chancery Poison Pill Suit Deal, Law360.com (February 10, 2021), available at https://www.law360.com/articles/1354310/tribune-publishing-class-near-chancery-poison-pill-suit-deal.

[22] See Shan Li, American Apparel, ousted founder trade power plays, Los Angeles Times (June 30, 2014), available at https://www.latimes.com/business/la-fi-american-apparel-20140701-story.html.

[23] For clarity, note that we use the term “acquiror” in Section V generally to indicate a party that acquires the company’s shares, which could include a party intending to acquire the entire company or an activist seeking a significant stake.

[24] Deal Point Data; this statistic excludes NOL rights plans.

[25] The full definition of “Distribution Date” would typically be the earlier of (i) the close of business on the tenth day after the public announcement that a person or group of affiliated or associated persons has become an acquiring person or such earlier date, as determined by the board, on which an acquiring person has become such and (ii) the close of business on the tenth day (or such later date as the board shall determine prior to such time as any person or group of affiliated or associated persons becomes an acquiring person) after the date that a tender or exchange offer by any person is first published or sent or given, the consummation of which would result in such person becoming an acquiring person.

[26] The last look provision will only become relevant where an acquiror intentionally triggered the rights plan. As discussed in Section II, most rights plans contain an inadvertent trigger provision, which allows the board to determine that the rights plan was not triggered if the acquiror inadvertently exceeds the triggering percentage.

[27] A rights plan with a qualifying offer provision is also sometimes called a “chewable pill.”

[28] Some qualifying offer provisions automatically exempt the offer from the rights plan if the offer meets the defined criteria and the board has not redeemed the outstanding rights or exempted such offer within a specified amount of time after the offer has commenced.

[29] Deal Point Data.

[30] A board should note that, if they adopt a rights plan, even without a qualifying offer provision, if an offer is made, they have a fiduciary obligation to consider whether terminating the rights plan or otherwise allowing the offer to proceed would be in the best interests of the stockholders.

[31] ISS proxy voting guidelines provide that, when considering whether to recommend that stockholders approve a rights plan that is put to a stockholder vote, the rights plan should contain a stockholder redemption feature – specifically, if the board refuses to redeem the rights 90 days after a qualifying offer is announced, 10% of the shares should be able to call a special meeting or seek a written consent to vote on rescinding the rights. See ISS United States Proxy Voting Guidelines Benchmark Policy Recommendations, published Nov. 19, 2020, available at https://www.issgovernance.com/file/policy/active/americas/US-Voting-Guidelines.pdf. This is different from the policy applied by ISS to determine whether to recommend votes against directors with respect to the adoption of a rights plan without stockholder approval, which calls for, among other things, a term of less than one year but not a qualifying offer provision.

Similarly, Glass Lewis will consider recommending that stockholders vote in favor of a rights plan that is put to a stockholder vote with a qualifying offer provision in which (a) the offer is not required to be all cash, (b) the offer is not required to remain open for more than 90 business days, (c) the offeror is permitted to amend, reduce or otherwise change the terms of the offer, (d) no fairness opinion is required and (e) there is a low to no premium requirement. See Glass Lewis 2020 United States Proxy Paper Guidelines, available at https://www.glasslewis.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Guidelines_US.pdf.

[32] The rights plan would typically define “fully financed” to mean that the offeror has sufficient funds for the offer and related expenses, as evidenced by (1) firm, legally binding written commitments from responsible financial institutions having the necessary financial capacity, subject only to customary terms and conditions, (2) cash or cash equivalents then available to the offeror, set apart and maintained solely for the purpose of funding the offer, or (3) a combination of the foregoing.

[33] In addition to accelerating the date on which the rights expire, rights plans also permit the board to redeem the rights for a nominal sum (often $0.0001 per right) before they become exercisable. In practice, however, rights are never redeemed, but instead the rights plans are amended so that the rights expire before they become exercisable. Amending the rights agreement avoids the need to execute the administratively difficult mechanic of paying each stockholder a nominal sum per right and does not require the company to disburse cash.

[34] Deal Point Data; this statistic excludes NOL rights plans.

Spencer D. KleinGlobal Co-Chair of M&A Practice

Spencer D. KleinGlobal Co-Chair of M&A Practice Michael G. O'BryanPartner

Michael G. O'BryanPartner Joseph SulzbachPartner

Joseph SulzbachPartner