MoFo 2020 Asia Buyouts Report: Update on Deal Terms – II. Fair Disclosure

MoFo PE Briefing Room

MoFo 2020 Asia Buyouts Report: Update on Deal Terms – II. Fair Disclosure

MoFo PE Briefing Room

We looked at 28 deals across Asia signed or closed pre-COVID-19 in which the buyer or a group of affiliated buyers acquired all or a significant majority of the outstanding equity of the target. We examined the common key terms in these deals and have sought to provide our insights on the patterns that the results reveal.

Approximately one-third of these deals involve a target in Southeast Asia and another third involve a target in Korea, with 25% involving a target in China or Hong Kong and 7% involving a Japanese target.

Following Part I of our Report on consideration mechanics, this week we will be looking at how sellers qualify their warranties by disclosures. In summary:

Under common law, a buyer may not be able to recover damages for a breach of representation or warranty where it has actual knowledge of certain facts or information that cause such representation or warranty to be inaccurate. As such, in share purchase agreements (SPAs), buyers often seek to introduce wording to the effect that representations and warranties given by the sellers are only qualified by matters fully, fairly, and specifically disclosed in the disclosure letter or the data room and not by any other information of which the buyers have knowledge, whether actual, constructive, or imputed (such provisions that retain for the buyers the benefit of representations and warranties even if the buyer has knowledge of the breach or fact are referred to as “pro-sandbagging clauses”). On the other hand, sellers will seek to include into SPA provisions that deny the buyers the benefit of representations or warranties to the extent the buyer has knowledge of the relevant breach or fact (referred to as “anti-sandbagging clauses”).

In some civil law jurisdictions in Asia (e.g., Japan), in the absence of other provisions, the default position is similar to that in common law – that is, a buyer may not be able to sue for a breach of representation or warranty where it has actual knowledge of or should have been aware of such breach prior to signing of the SPA. That said, in those jurisdictions, a schedule appended to the SPA (a “disclosure schedule”) disclosing specified facts and/or information that breach the representation or warranty is usually the sole exception to such representation and warranty. In exceptional cases where the disclosure is not limited to facts and information in the disclosure schedule (e.g., disclosure covers the data room) and disclosure is not defined to exclude non-specific facts and inferences that can be drawn from the information in the data room, the court may find in favor of the seller if the buyer has been grossly negligent in not having identified the breach from the information disclosed in materials provided to the buyer. On the other hand, the court may find in favor of the buyer if appropriate pro-sandbagging clauses are included in the SPA (to the effect that the seller cannot exclude its liability even if the buyer should or would have been aware of the relevant breach or fact).

Seventy-five percent of SPAs governed by Hong Kong law (among the 28 deals we studied) require sellers to make fair disclosure before they can exclude their liabilities based on such disclosure (50% with detailed “fair disclosure” definitions); 66.7% of SPAs governed by Singaporean law contain similar fair disclosure provisions (all defined in detail); 50% of SPAs governed by Korean law contain such provisions (30% of them define “fair disclosure” further in the SPAs).

No SPAs governed by Japanese law contain fair disclosure language. This is consistent with our understanding of the market practice in Japan described in the preceding section. In one of the Japanese SPAs that include the data room as part of the disclosure, the buyer did not negotiate for a pro-sandbagging clause and may have taken comfort from the default position under Japanese law, which makes it difficult for a seller to claim that a buyer should have been aware of the relevant information in order to defeat the buyer’s claim for breach of representation.

No SPAs governed by PRC law in our sample deals contain fair disclosure language. In the PRC, disclosure is sometimes loosely defined as a result of the customary practice of the local legal practitioners. However, when established PRC law firms and international law firms are involved in SPA negotiation, “disclosure” is more often defined and limited.

“Disclosure” is usually defined in both the SPA and, if W&I insurance is used, the W&I policy. In the latter case, W&I insurers often amend the definition in the SPA to something with which they are more comfortable, and the policy definition can also be negotiated.

Often, a very well-advised buyer will include one of the following into the definition of “disclosure” to limit the ability of the seller and/or W&I insurer to argue that there was a disclosure and thus a buyer’s claim is unsubstantiated:

Any definition that weakens or eliminates the wording in brackets as set out above would give the seller and/or W&I insurer a better chance of succeeding in an argument that there was a disclosure with respect to a specific claim by the buyer.

In deals following the approach in the UK market, a seller’s disclosures against the representations and warranties are typically contained in a separate disclosure letter, rather than in schedules to the SPA itself. The disclosure letter usually contains “general disclosures” (e.g., information that can be revealed by a search at the companies registry or courts), which qualify all representations and warranties given by the seller, and “specific disclosures,” which, although usually cross-referenced to specific warranties, parties often agree also constitute disclosures against all other warranties.

In many cases, sellers will seek the contents of the documents contained in the data room (if there is one) to be treated as part of the “general disclosure,” and buyers will usually resist wholesale disclosure of a data room.

Even if buyers successfully push back on the inclusion of the entire data room as part of the “general disclosure,” often copies of documents are appended to the disclosure letter (such documents often called the “disclosure binder”), and sellers will seek for the entire contents of the documents contained in the disclosure binder to be disclosed against all the representations and warranties.

In the United States and, as mentioned above, Japan, the market practice is different. It is customary for buyers to allow specific disclosures only in respect of each representation and warranty against which disclosure is being made and set out a negotiated schedule appended to the SPA. “General disclosures” are not common, and “specific disclosures” in relation to a warranty are often not treated as effective disclosures in relation to all other warranties unless specifically cross-referenced.

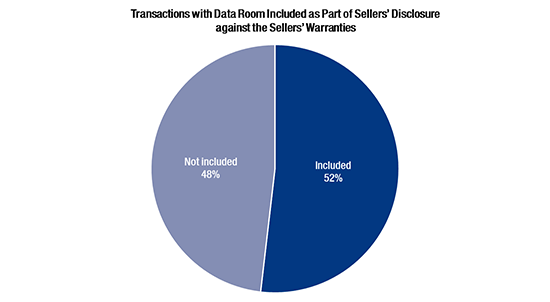

In our sample deals, 52% of the share purchase agreements refer to sellers making general disclosure of the contents of the data room.

Does the fact that data room disclosure is not found in 48% of the SPAs necessarily mean that the UK practice of allowing such general disclosure is becoming less common in Asia and the U.S. practice of requiring specific disclosure in a schedule to the SPA is now being more widely adopted? Our view is that is not necessarily the case. It is important to bear in mind that we are looking at a subset of transactions that are buyouts only, and W&I insurance is commonly used in buyout deals. Where W&I insurance is taken up by one of the parties, often the relevant SPA does not provide for general disclosure of the data room because W&I policy will usually deem the disclosures made in the data room as part of the general disclosures under the policy.

If the parties prefer a more U.S.-style specific disclosure (i.e., no data room is to form part of the disclosure against the warranties), then the price of the W&I insurance is likely to increase to a price that is more closely aligned to the pricing of the U.S.-style W&I insurance policies (usually at 20-30% additional premium for U.S.‑style non-disclosure of data room, compared to the premium that would have been charged for the same transaction if a UK-styled fair disclosure based on the contents of the data room is permitted by the buyer).

Where the buyer has accepted a “general disclosure” of the data room as a matter of principle, arguably anything therein can be considered fairly disclosed. However, in practice, whether information is “fairly” disclosed tends to turn on whether there is sufficient specific detail for the buyer to assess and understand the significance of the information disclosed.

Presentation also matters. There is case law that suggests that a mere reference to a source of information, that was complex and a diligent enquirer might or might not find the relevant information, would not satisfy the requirements of fair disclosure. A seller would have a much stronger argument that disclosure of information in a data room is clearly and fairly disclosed, if the relevant information is presented in a well-organized manner and if the relevant information is highlighted or summarized in the disclosure letter or an appendix index to it and not merely buried in an obscure document that is part of a data dump. For this reason, careful sellers tend to take time not only to provide complete and sufficiently detailed information but also to index, organize, and/or summarize it.

When facing individual sellers, all buyers managed to limit the sellers’ disclosure by including some form of fair disclosure language. This indicates that, where buyers may have a low level of confidence with how disclosures are prepared by the sellers, buyers will always insist on limiting sellers’ disclosure by including the concept of “fair disclosure.”

Sixty-three percent of financial buyers in our sample set included the concept in their SPAs, which is significantly higher than the percentage of strategic buyers that picked up the importance of including the concept (only 42% of the strategic buyers managed to build some form of “fair disclosure” definition or language into their SPAs).

If the seller or the W&I insurer considers it economically worthwhile to defend or investigate a claim under an SPA with a “fair disclosure” provision, the standard procedure is for its legal counsel to comb through the data room to seek to establish that there was fair disclosure of the matters about which the claimant is making the claim.

The seller’s or the W&I insurer’s counsel will develop a series of defenses and, in the case of the W&I insurer, follow-up requests for information. In a process driven by a W&I insurer, very often, the W&I insurer and the claimant will settle on an amount because the W&I insurer is well aware that the legal cost of dragging on a claim may exceed the claim amount and would far exceed the premium, and W&I insurers are generally keen to make it known to the market that they are “willing to pay” under their policies and that the W&I insurance products are worth purchasing.

On the trends of claim settlement, claims are on the rise worldwide (including during the period when COVID‑19 impacted the global economy) and so are the number of claims being paid. As a result of the increase in the number of claims, certain W&I insurers have increased their pricing though the market remains competitive for W&I insurers.

Our litigation team’s experience is that buyers that have purchased W&I insurance are generally keen to make claims, as once they have paid the premium, they have nothing to lose by initiating claims, and there is always an incentive for them to try to get their money’s worth. The bigger or the higher the value of a transaction is, the more likely the insured would seek to make a claim, but W&I insurers generally still prefer to insure higher value deals. This is also consistent with what AIG found in its statistics AIG[1]: for deals of over USD 100 million, there is one claim for every five policies purchased; for deals of less than USD 100 million, the average claim frequency is only 17%.

It is important for sellers who desire to limit their exposure under the representations and warranties to bear in mind the following:

If you are interested in the content of our full report, please reach out to us, and we will be happy to discuss other aspects of the report with you.

* Morrison & Foerster Trainee Solicitors Vivien Chiu and Jacky Lam also made contribution to this article.

[1] “AIG Claim Intelligence Series - M&A: A rising tide of large claims” (2020).