Personalized Medicine Claims Get a Boost under New MPEP Revision

The United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) published the latest revision to its Manual of Patent Examining Procedure (MPEP) on June 30, 2020. According to the Executive Summary, in this revision, nearly all of the 27 chapters have been updated to incorporate new case law and Patent Office procedures. Some of the most noteworthy updates for practitioners relate to examination of subject matter eligibility for life science inventions and could have a significant impact on the examination of personalized medicine claims.

Section 2106 of the MPEP provides the analytical framework for assessing subject matter eligibility under 35 U.S.C. § 101 as set forth by the Supreme Court in Alice v. CLS Bank and Mayo v. Prometheus.[1]

Step 1 asks whether the claim is directed to a statutorily eligible category (process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter). If the answer is yes, the analysis proceeds to Step 2A.

Step 2A asks whether the claim is directed to a judicial exception (a law of nature, a natural phenomenon, or an abstract idea). If the answer is yes, the analysis proceeds with Step 2B.

Step 2B, also sometimes called the search for an inventive concept, asks whether the claim as a whole amounts to significantly more than the judicial exception itself.

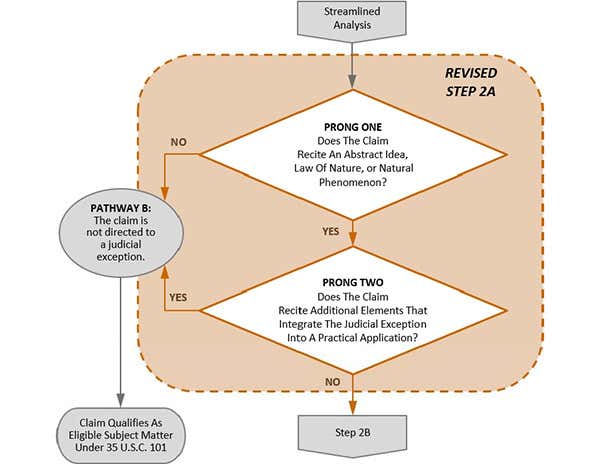

In this revision, the USPTO has now clarified that Step 2A itself is a two‑prong test.[2] In the first prong of Step 2A, the question is whether the claim recites an abstract idea, a law of nature, or a natural phenomenon.[3] In the second prong, the question is whether the claim recites additional elements that integrate the judicial exception into a practical application.[4] The flowchart below is reproduced from MPEP Section 2106.04, which summarizes the new two-pronged approach to Step 2A.

The MPEP acknowledges that Step 2A Prong 2 is similar to Step 2B (whether the claim as a whole amounts to significantly more than the judicial exception) but cites an important distinction. Specifically, Step 2A Prong 2 explicitly excludes consideration about whether the additional elements of a claim are routine and conventional activity.[5] The MPEP states that “additional elements that represent well‑understood, routine, conventional activity may integrate a recited judicial exception into a practical application.”[6]

New Section 2106.04(d) provides detailed discussion of how to assess whether a judicial exception is sufficiently integrated into a practical application in order to confer subject matter eligibility on a claim. Several example analyses of new Step 2A Prong 2 are provided based upon recent Federal Circuit cases. Improvement in the functioning of a computer is an example given for integrating a judicial exception into a practical application for high-tech inventions.[7]

For life science inventions, treatment or prophylaxis of a disease is provided as an example of adequately integrating a judicial exception into a practical application.[8] This example is based upon the Vanda v. West-Ward Federal Circuit decision.[9] In Vanda, the claims recited a method of treating a patient having schizophrenia with iloperidone by performing a genotyping assay to determine if the patient has a particular genotype and administering iloperidone at a certain dosage range depending on the genotype.[10] The court distinguished Mayo because the Vanda claims recited administering a drug at a particular concentration based upon the genotype, an application of a natural law.[11] On the other hand, in Mayo, the claims were directed to a diagnostic method based on the relationship between concentrations of certain metabolites and the likelihood that a drug would be effective, but the administration step was deemed to be “akin to a limitation that tells engineers to apply a known natural relationship.”[12]

The MPEP provides several criteria for assessing treatment or prophylactic claims. As an initial matter, the claim must affirmatively recite an action that effects treatment or prophylaxis for a particular disease, such as administering a drug.[13] Steps, such as prescribing a drug or claims that recite a “pharmaceutical composition,” will not be treated as sufficiently integrating a judicial exception into a practical application.[14]

Three additional factors are considered regarding subject matter eligibility of treatment or prophylactic claims:

1. The particularity or generality of the treatment or prophylaxis.[15]

2. Whether the limitation has more than a nominal or insignificant relationship to the exception.[16]

3. Whether the limitation is merely extra-solution activity or a field of use.[17]

For each factor, the MPEP provides useful examples of claim limitations that would or would not be sufficient. For example, a limitation that recites administering a particular amount of a particular drug based upon a genotype is considered to be sufficiently particular under the first factor, whereas merely reciting “administering a suitable medication to the patient” is too general.[18]

The table below provides additional exemplary life science claims that are likely subject matter eligible under new Step 2A Prong 2 or are likely not directed to eligible subject matter.

Likely eligible | Likely ineligible |

1.[19] A method of treating cancer in an individual comprising i) determining whether the cancer expresses protein X, and ii) if the cancer expresses protein X, administering an anti-X antibody to the individual. | 1. A method of treating cancer in an individual comprising i) determining whether the cancer expresses protein X, and ii) selecting a treatment based upon whether the cancer expresses protein X. |

2.[20] A method of treating diabetes in an individual comprising i) detecting the level of blood glucose of the individual, and ii) administering 5-10 units of insulin to the individual if the blood glucose level is above 250 mg/dl. | 2. A method of treating diabetes in an individual comprising determining the level of blood glucose of the individual, wherein a blood glucose level of greater than 250 mg/dl indicates that the individual should be administered insulin, and wherein a blood glucose level of less than 250 mg/dl indicates that the individual should not be administered insulin.

|

3.[21] A method of vaccination comprising i) administering a vaccine to a group of individuals according to different vaccination schedules, ii) analyzing the vaccine response of the individuals to determine a low risk vaccination schedule, and iii) vaccinating a second group of individuals according to the low risk vaccination schedule.

| 3.[22] A method of determining a vaccination schedule comprising i) administering a vaccine to a group of individuals according to different vaccination schedules, and ii) analyzing the vaccine response of the individuals to determine an optimal vaccination schedule.

|

In the newest revision of the MPEP, the USPTO provides important updates to harmonize the manual with recent Federal Circuit case law.[23] The updates to the subject matter eligibility section in the MPEP will be useful to life science practitioners, as the MPEP clearly lays out the analysis for claims that involve treatment or prophylaxis. Importantly, the new two-prong analysis of Mayo/Alice Step 2A explicitly does not take into account whether the additional elements beyond the judicial exception are routine and conventional. This update should help patent applicants with personalized medicine claims establish subject matter eligibility in Step 2A and avoid Step 2B, where it can be difficult to establish an inventive concept for such claims if conventional detection and/or treatment methods are used.

[1] See Alice Corp. v. CLS Bank International, 573 U.S. 208 (2014), and Mayo Collaborative Services v. Prometheus Laboratories, 566 U.S. 66 (2012).

[2] MPEP Section 2106.04 (II)(A).

[3] MPEP Section 2106.04 (II)(A)(1).

[4] MPEP Section 2106.04 (II)(A)(2).

[5] MPEP Section 2106.04(d)(I). In contrast, other Step 2B considerations, such as the conventionality of an additional element, are often evaluated. See MPEP Section 2106.05.

[6] Id.

[7] Id.

[8] Id.

[9] Vanda Pharmaceuticals Inc. v. West-Ward Pharmaceuticals International Limited, 887 F.3d 1117 (Fed. Cir. 2018).

[10] Vanda at 1121.

[11] Vanda at 1135.

[12] Id. citing Mayo Collaborative Services v. Prometheus Laboratories, Inc., 565 US 66 (2012), at 78.

[13] MPEP Section 2106(d)(2).

[14] Id.

[15] MPEP Section 2106(d)(2)(a).

[16] MPEP Section 2106(d)(2)(b).

[17] MPEP Section 2106(d)(2)(c).

[18] MPEP Section 2106(d)(2)(a).

[19] See MPEP 2106.04(d)(2)(a) regarding the particularity or generality of the treatment or prophylaxis.

[20] See MPEP 2106.04(d)(2) discussing the Vanda claims.

[21] See MPEP 2106.04(d)(2)(c) regarding limitations as extra-solution activity.

[22] See MPEP 2106.04(d)(2)(c) regarding limitations as extra-solution activity.

[23] This revision incorporates changes effective on or before October 2019 and, therefore, does not include the Illumina v. Ariosa Federal Circuit case decided in March 2020, which added an additional basis for subject matter eligibility in life sciences for claims directed to methods of preparation. Illumina Inc. v. Ariosa Diagnostics Inc., No. 2019-1419 (Fed. Cir. March 2020). See a discussion of the Illumina case. Subsequent revisions to the MPEP will likely incorporate the Illumina case.

Meghan McLean Poon, Ph.D.Partner

Meghan McLean Poon, Ph.D.Partner

Practices

Industries + Issues