Data Center Investments in China: Cloud 9 for Foreign Investors?

MoFo PE Briefing Room

Data Center Investments in China: Cloud 9 for Foreign Investors?

MoFo PE Briefing Room

Internet data center (“IDC”) projects in China have attracted ever-increasing investment interest from investors outside of China. Post-COVID-19 outbreak, this sector has become even hotter as more businesses seek to move online, thus driving greater demand for cloud storage space. Since April 2020, the Chinese central and local governments have issued a number of policies to further encourage the development of “new infrastructure construction” (新基建) projects to boost economic recovery, including “large scale data centers” (大数据中心).

Foreign direct investment in the IDC sector has been limited due to the significant restrictions on foreign-invested entities applying for the type of value-added telecommunications services license required to operate an IDC business in China (an “IDC License”). Currently, there are a number of structures through which non-Chinese companies can obtain exposure to IDC projects in China despite these restrictions. We consider, below, the risks and benefits of each of the commonly used structures.

Although, in general, foreign-invested companies are not currently permitted to apply for IDC Licenses, Chinese JVs that are up to 50% owned by either Hong Kong or Macao companies that meet the requirements of the Mainland and Hong Kong/Macao Closer Economic Partnership Arrangement (“CEPA”) are permitted to apply for IDC Licenses.

Unfortunately, investors from jurisdictions other than Hong Kong or Macao cannot simply incorporate a Hong Kong or Macao company and use that company to invest in a Chinese JV. In order to be CEPA qualified to invest in an IDC JV in China, a Hong Kong/Macao company must meet certain qualifications, including the following:

According to a report published by the China Academy of Information and Communications Technology, as of March 2020, 13 JVs established under the CEPA route have obtained IDC Licenses in China. The Hong Kong/Macao-based investors behind these JVs include some of the primary telecommunications service providers in Hong Kong and Macao, such as PCCW/HKT and CITIC Telecom.

Some foreign companies, such as SAP, NTT and Atos, that are not headquartered but have subsidiaries and established operations in Hong Kong or Macao have also been able to set up JVs with Chinese partners through such subsidiaries to obtain IDC Licenses in China through the CEPA route. However, it is very challenging in practice to obtain an IDC License in China through the CEPA route as the PRC authorities have wide discretion in the approval process and the timeframe for approval is highly uncertain.

The VIE or “variable interest entity” structure is the structure most commonly used by foreign investors to invest indirectly into IDC projects in China. Among others, GDS Holdings Limited and 21Vianet Group, Inc., both of which are NASDAQ-listed companies, have adopted the VIE structure for their IDC businesses in China. In addition to being used for investments in the IDC sector, the VIE structure is best known for being used by U.S.- and Hong Kong‑listed companies, such as Alibaba, Tencent and Baidu, in the Internet content, e-commerce and online payment processing sectors. It has also been used in many other sectors in which foreign investment in China is restricted, such as education and media.

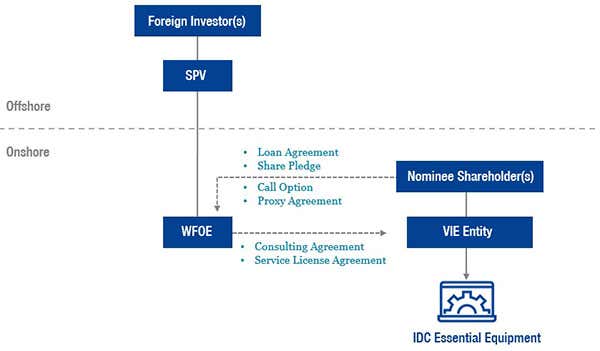

As illustrated in the chart below, under the VIE structure, the foreign investor establishes a wholly foreign-owned enterprise in China (the “WFOE”) that enters into a suite of contracts with a wholly domestically owned entity that holds an IDC License (the “VIE Entity”) and certain PRC individuals who serve as the nominee shareholders of the VIE Entity. Through those contracts, the WFOE obtains indirect control over the governance of the VIE Entity and obtains the substantial majority of the profits of the VIE Entity. Importantly, from the perspective of a potential future listing, based on this suite of contracts, accounting standards permit (or, more precisely, require) the foreign investor to consolidate the financials of the VIE Entity even though it has no direct equity investment in the VIE Entity.

Although the VIE structure is generally viewed as being in a grey area under PRC law that is not clearly permitted or prohibited, it has been extensively used in China for 20 years. The continuing existence and validity of the VIE structure came into question on January 19, 2015, when the Ministry of Commerce of the PRC released, for public comment, a draft of the Foreign Investment Law (the “FIL”), which reflected a clear intent to restrict usage of the VIE structure as a way to circumvent Chinese foreign investment rules. Yet, the final version of the FIL that was enacted on March 15, 2019, and became effective on January 1, 2020, contains no provisions concerning VIEs, leaving the VIE structure, once again, in a grey area.

An interesting recent development is that, on April 20, 2020, the PRC State Administration for Market Regulation officially accepted, for the first time in history, a merger control filing for concentration of operators (an “AML Filing”) in respect of a transaction in which the VIE structure was adopted. Before this, it was market practice not to make an AML Filing with respect to transactions involving VIE arrangements, as it was the widely held view among stakeholders that PRC authorities generally would not accept AML Filings involving VIE structures, so as not to be seen as “endorsing” the VIE structures by accepting or clearing AML Filings (see our previous article on this topic here).

These recent developments indicate that, while the VIE structure is technically still in a grey area, the use of VIE structures by foreign investors to invest indirectly in IDCs in China is unlikely to be an enforcement target of the PRC government in the near future.[1] On the other hand, although the VIE structure gives foreign investors contractual control approximating direct equity ownership, such structure may, in practice, be less effective than direct equity ownership.[2] Authorities may also raise transfer-pricing concerns and question the fees charged by WFOEs in related-party transactions, and the revenue transferred from the VIE Entity to the WFOE may be negatively affected.

In other cases, foreign investors may tap the PRC IDC market through commercial cooperation with local Chinese partners that are IDC License holders, primarily through one of two models: the Technical Support Model and the Co-Investment Model. As opposed to the JV and VIE structures discussed above, the commercial cooperation models afford foreign investors a relatively more straightforward and practical path to investing in the IDC sector in China that does not involve a highly uncertain approval process under the CEPA route or any “grey area” issues in connection with a VIE structure. Note, however, that, as in the case of the VIE structure, under both of these commercial cooperation models, only the PRC business partners (or the VIE Entity, in the case of the VIE structure), as IDC License holders, can directly contract with customers and provide IDC services for fees.

Microsoft has used the Technical Support Model by cooperating with 21Vianet Group, Inc., a primary IDC service provider in mainland China and a NASDAQ-listed company, to provide its Azure cloud services in mainland China.

Under a typical Technical Support Model, the foreign investor generally licenses its brand and technologies, directly or indirectly through a WFOE, to the Chinese IDC License holder and also provides related technical maintenance and support services by charging licensing and service fees.

Unlike in a VIE Structure, a foreign investor or its subsidiary WFOE does not control the governance of the IDC License holder through a nominee arrangement but, instead, depends on contractual covenants and restrictions. With a set of robust covenants and restrictions imposed on the PRC IDC License holder in its operations in the relevant license and service agreements, the foreign investor can play an important role in the way the IDC business is operated. It is both lawful and commercially essential for the brand and technology licensor to be actively involved in the quality control process to ensure the relevant services rendered by the licensee are up to the licensor’s standard. In the case of a material breach, the licensor generally has a right to terminate the licenses – these rights serve as “teeth” to substantially mitigate the risks of noncompliance.

A well-structured Technical Support Model can therefore provide foreign investors with strong operational control and a steady revenue stream through licensing and service fees. Foreign investors can also combine the Technical Support Model with the VIE structure or the Co-Investment Model to take a larger stake in the IDC business and/or finance acquisition of real estate and the construction of IDC infrastructure.

Strategic investors, such as KDDI and Equinix, and private equity investors, such as KKR, have invested in the IDC sector in China through the Co-Investment Model. KDDI invested in four IDCs in Beijing and Shanghai, through participation in the constructions of the IDCs and provision of ancillary services to the IDCs. Equinix invested in an IDC project in Shanghai in cooperation with Datang Gaohong Information Technology Co., Ltd. KKR invested in an IDC project in Kunshan, Jiangsu Province, through cooperation with Golden Data (Kunshan) Information Technology Co., Ltd.

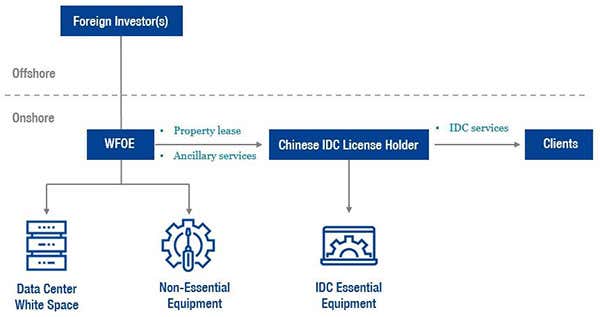

Under the Co-Investment Model, the Chinese IDC License holder owns the racks, IT equipment, database and network facilities of the IDC (collectively, the “IDC Essential Equipment”) and provides the IDC services that require its personnel to touch the servers, while the WFOE (the subsidiary of the foreign investor established in China) acquires the real estate and constructs the IDC and then leases the property to the IDC. The WFOE also provides certain non-telecommunications services, such as property management, equipment maintenance, security and cleaning services to the IDC.

As illustrated in the chart above, a notable benefit of the Co-Investment Model is that it allows the foreign investor, through its PRC subsidiary, to construct the IDC white space and own the real estate itself. Thus, this model considerably simplifies the issue of how to finance the capital investment required to purchase real estate and construct the IDC that arises under the Technical Cooperation Model and the VIE structure. It also allows the WFOE to take advantage of the depreciation of these assets on its financial statement.

If a foreign investor seeks to list the IDC business on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange through an IPO down the road, it could adopt a hybrid model using a VIE structure to operate the IDC business and a Co-Investment Model to house the real estate assets. Such a bifurcated structure is also responsive to the requirement of the Hong Kong Stock Exchange that any VIE structure adopted by a prospective listing company be narrowly structured – that is, it should only be used for business lines in China in which foreign investment is restricted or prohibited under PRC law.

On August 15, 2019, 10 Beijing local authorities, including the local branches of the Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM) and the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), jointly issued a three-year action plan (the “Opening-Up Plan”) to further open certain services sectors in Beijing to foreign investment. The Opening-Up Plan sets out measures to allow and attract greater foreign direct investment in a wide range of sectors, including allowing up to 50% foreign investment in IDC services.

However, it remains to be seen how the Opening-Up Plan will be formally implemented. No detailed implementation rules have been promulgated so far. Despite the Opening-Up Plan being a welcome initiative, with more localities likely to be eager to follow Beijing’s example, the PRC central government may not want the liberalization of foreign investment in this sector to spread beyond Beijing at the moment. In any case, the plan proposes to allow up to only 50% foreign investment in IDC services.

As such, foreign investors will likely continue to use one or a combination of the structures outlined above in order to indirectly invest in up to 100% of an IDC – this may include a direct equity stake to the extent permitted by the opening up of the sector.

Currently, IDC businesses in China are primarily concentrated in the first-tier cities of Beijing, Shanghai, Shenzhen and Guangzhou. As the IDC market in these areas continues to mature and become saturated, the authorities in these cities have started to restrict new IDC projects or impose heightened approval requirements for new IDC projects in their localities. On the other hand, local governments can be considerably more welcoming, with cities in western and central China even offering preferential tax treatment and other incentives to attract new investments. In addition, the costs of certain key resources, such as land and power supply, can be substantially lower in these areas as compared to those in first-tier cities. Thus, foreign investors are also increasingly attracted to IDC investments in non-first-tier cities.

As in other jurisdictions, mainland China has implemented data localization requirements and data export restrictions. The PRC Cybersecurity Law that became effective on June 1, 2017, requires that operators of “critical information infrastructure” must store “personal information” and “important data” collected through their operations in China within China unless there is a genuine business need to transfer such information abroad provided that they have conducted a security assessment. In May and June 2019, the Chinese authorities issued the new draft Measures for Data Security Management and the new draft Measures on Security Assessment of the Cross-Border Transfer of Personal Information for public consultation, which contemplate expanding the scope of the requirement to undertake a security assessment, such that it not only applies to the operators of “critical information infrastructure” but also to general network operators. In general, we expect that more stringent and detailed data localization requirements will be put in place as the Chinese government continues to strengthen its enforcement in this regard. These data localization requirements have, in fact, contributed to the increased need for local IDC services in mainland China and have also required existing IDC service providers to devote more resources to ongoing regulatory compliance.

We expect that, despite regulatory hurdles and the evolving nature of applicable legislation, the increase in foreign investment in the IDC sector in China will continue to be strong as the sector itself continues to expand exponentially.

[1] Note that the level of risk involved in the use of a VIE structure is generally higher if the ultimate controller behind a VIE structure is a pure foreign investor, as opposed to a VIE structure where the ultimate controlling shareholder is actually a Chinese individual or entity that has established an offshore structure by way of “round-trip investments” to facilitate an overseas listing.

[2] See our article on the VIE structure that was published in Hong Kong Lawyer for a complete analysis of the risks involved in using the VIE structure.

As further explained in the Terms / Notices linked below, the information provided herein does not constitute legal advice. Any information concerning the People’s Republic of China (“PRC”) is not intended and shall not be deemed to constitute an opinion, determination on, or certification in respect of the application of PRC law. We are not licensed to practice PRC law.